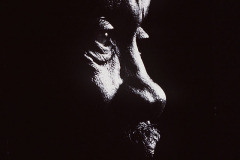

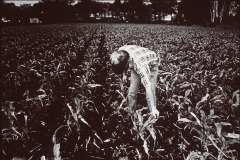

Forty years ago, a photographer named Dallas Kinney won The Palm Beach Post’s first (and only) Pulitzer Prize for Migration to Misery. It was a series of photographs of migrant farm workers who made the circuit from North Carolina to South Florida following the harvesting seasons.

Forty years ago, a photographer named Dallas Kinney won The Palm Beach Post’s first (and only) Pulitzer Prize for Migration to Misery. It was a series of photographs of migrant farm workers who made the circuit from North Carolina to South Florida following the harvesting seasons.

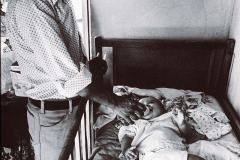

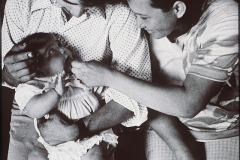

Dallas’ work is one of the things that drew me to The Post. I never came close to winning a Pulitzer, but I spent months and months – most of it on my own time – in the farming areas around Belle Glade, Pahokee and Immokalee in Florida documenting as much as I could about how produce gets to our tables.

Woodie and Arlo Guthrie’s Deportees

At some point, I heard Arlo Guthrie singing his dad’s song, Deportee (Plane Wreck at Los Gatos), an account of a “skyplane” that blew up over Los Gatos canyon while it was flying illegal workers back to Mexico. The news accounts listed the names of the flight crew, but as far as the 27 men and one woman being deported, the “radio says they are just deportees.”

No name but “Wetback”

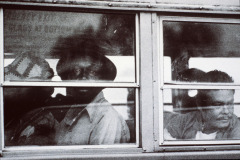

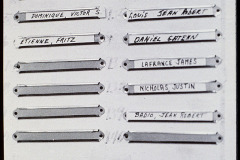

That song came to my mind when I was hanging around the Collier County Stockade when the Border Patrol was making one of its sweeps. Since they were “detainees” and not inmates, the stockade officials didn’t track their names, just the count.

They were known by no name except “Wetbacks.”

Over the years, I married the photos and song into a slide show I used for dog and pony shows. I’d post it that way, except that it would violate Copyright and YouTube would pull it down.

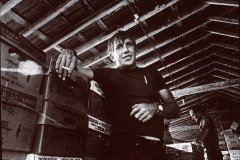

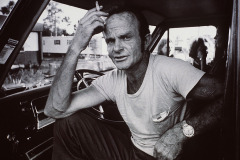

Gallery of farm worker photos

Click on the first image, then click on the sides to move through the gallery. The lyrics to the song, Deportees are the title of each picture (at the bottom left).

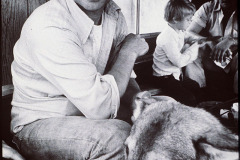

[Editor’s note: some of the photos may not be of the best quality. They are second or third generation copies of second-quality prints left over after I sent the best ones to engraving. Some day I’ll get around to scanning the original negatives, but not this time.]

Brings back some better-left-buried memories of my time at Palm Beach newspapers. I had the priviledge of briefly knowing Dallas, and spent way too much time in Belle Glade. (Five minutes was too much time.) For a middle class white boy from Cape, it was a shot of reality. Honestly, Belle Glade made Smelterville look like North Palm Beach.

Bill,

Belle Glad so resembled a third-world country that the State Department would send people there for training.

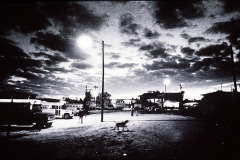

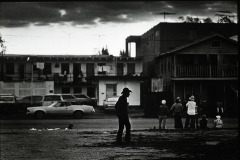

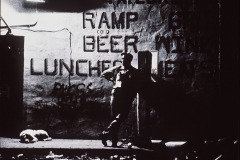

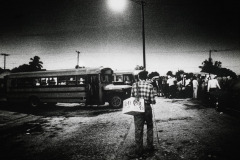

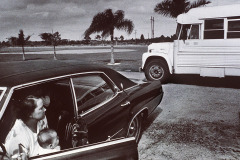

A lot of the pictures were taken at Belle Glade’s Loading Ramp, a block-square area where labor buses would come to pick up workers in the pre-dawn hours. With one exception, when I finally got a reporter assigned to the story, I was usually the only white face for blocks, except for an occasional cop car.

The first visit was a little tense, because no one knew why I was there. The next time, I came back with a stack of prints from the first visit, a practice I continued. It didn’t take long before everyone knew who I was and was very protective of me. I can say that I never had a bad experience there.

I didn’t stray far from the Loading Ramp area, though. People who get up at 2 a.m. to get on a bus and pick produce from cain’t see to cain’t see aren’t the kinds of folks who make trouble.

My initial contact in Immokalee was the Collier County Stockade warden. I had seen a story about a labor contractor who had killed a worker and was serving a life sentence on the installment plan. He had managed to convince (buy off) a judge to let him serve his sentence a few months at a time off-season.

The warden, a good old boy, said, “Come on down, but I bet the guy will never serve another minute.”

He was right, but we hit it off and he put in a good word for me all over town. That’s the key to doing stories like this. You need one person, then it’s all about networking.

I found that most subjects will cooperate if you treat them with respect and dignity.

Your camera has led you through an amazing life, Ken! Not many of us have seen the invisible people.

Early in the great depression before it was exacerbated by the FDR spending programs, President Hoover ordered all illeagle aliens deported to make jobs available to American citizens who desperately needed work.

President Harry Truman deported 2,000,000 illeagl’s after WWll to create jobs for returning veterans.

Beginning in 1954 President Dwight Eisenhower deported 13,000,000 Mexican nationals! The program was called “Operation Wetback” so veterans from WWll and Korea would have a better chance at finding jobs.

While we were relatively sheltered in Cape during those years, I recall seeing, ironically, “The Enemy Below” at a theater in Baileys Harbor WI. A good way through(past the point where the German sailor gets his hand cut off) a federal agent appeared at the rear of the theater and requested everyone’s papers. Pandamonium ensued as many in the audience scrambled for the rear exits – where the feds had stationed trucks. Never did see the end of the movie.

We kept Momeo busy the rest of that purple people eater summer making pies with all the cherries we brought in from after-dark forays into the orchards, there not being enough pickers to get in the entire crop.

After I had developed a network of contacts in Immokalee, I was paired with Larry Mlynczak,one of the best reporters I ever worked with. We spent a week searching for The Bad Guy.

The Border Patrolman said, “Hey, I’m just enforcing the laws your representative voted for.”

The grocer said, “I’m operating on a 1% profit margin.”

The farmer said, “By the time I pay for fuel, fertilizer, labor and all of my operating expenses, I’ve gone in the hole for the past two years.”

The landlord who rented to illegals said, “They don’t cause me any trouble; they pay their rent on time; if they get rounded up, I just box up their things and hold on to them because they’ll be back.”

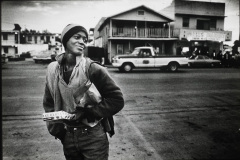

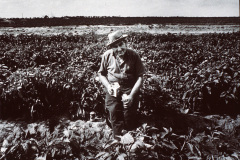

The workers are a mixed bag. I managed to convince a labor contractor to let Larry pick peppers for a day. At the end of the shift, he was handed $17 in cash, with a dollar withheld for Social Security. “When I retire, the first dollar I spend will be the one I earned picking those peppers,” he told me.

The crew we were on was mostly Anglo. One young guy really hustled. He was taking up the slack for his pregnant girlfriend, who couldn’t keep up. On a break, I said to him, “You’re a hard worker and seem to have some ambition. Why are you out here picking peppers for 17 bucks a day?”

“I have anger issues. I generally get fired for punching out my boss.”

Non-native workers send enough money home to their families that the small town has a post office much larger than you would expect for the population.

So, who, in the end, turned out to be The Bad Guy?

Well, like Pogo discovered, “We have met the enemy and he is us.”

As long as we want cheap peppers, tomatoes, corn and other produce, then we are contributing to the pressures that squeeze the lowest levels of our society.

Seems to me the country missed the chance to have a real debate on the points you raise in the last election, but we’re hearing about them now from Arizona. Perhaps the cheap food prices claimed aren’t as desireable as safety with Pheonix second only to Mexico City in kidnappings. By the way, where do you get those low rates?

I’m not going to get dragged into a political debate where there is going to be more heat than light.

Here are my observations.

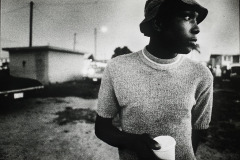

1. These photos were taken between 25 and 30 years ago. Most of the subjects were American Black citizens. Only a couple of them would be stopped, even in AZ, and asked for their papers.

The complexion of the work force would be completely different today. You would find workers from Mexico, Haiti and Central America doing that work. Why? Because they’ll work for wages that others won’t. Why aren’t wages higher? Because you want your food cheap. So cheap, in fact, that your tomatoes are probably coming from Mexico.

2. We have a two-bedroom house across the street from us that was rented to probably at least two dozen people. One of the landlords of an adjacent property wanted to know if we wanted to join him in a complaint. Our response: they don’t bother us; they don’t park in our spots, they don’t make noise; they greet us when they see us and they haven’t stolen anything.

The really ugly side of this story is that the home had been owned by some folks we know who got into some financial problems and unloaded the house to one of those buy-ugly-homes kind of outfits that was supposed to pay off the balance of the mortgage. THEY’RE the ones who rented the place, pocketing the money and never paying off the mortgage, something our friends didn’t find out until the bank came knocking.

I’d rather have the renters than the landlord any day.

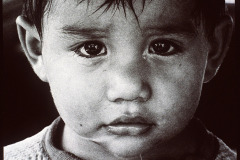

3. Anybody who is willing to risk their lives to come to the United States from Haiti in a tiny boat to flee tyranny and to make a better life for themselves and their families shows the kind of initiative that I applaud. They’ve got a work ethic that’s missing too often by folks who were born here. I’ve photographed the ones who didn’t make it – the ones who washed up on the beach dead.

4. I have the utmost admiration for folks who are willing to do jobs that I can’t or won’t do. You’d be eating your Big Mac without pickle, lettuce or tomato if you counted on me picking them for you.

If you want to debate immigration policies, take it somewhere else. One of the things I learned in the newspaper business is that Freedom of the Press belongs to he who has one.

I worked for publishers who had all kinds of personal quirks. One of my personal quirks is that if you want to comment, I would prefer that you use your real name.

While researching another piece, I ran across this in an Out of the Past column. (Some schools were let out during harvest season. I don’t remember if any Cape schools were among them.)

50 years ago: Sept. 9, 1954

Continuing need of labor in cotton fields of this area has resulted in certification for some 1,200 to 1,400 Mexican nationals in Sikeston area; needs in Cape Girardeau area can be filled without outside labor, if present indications hold, says spokesman for Missouri State Employment Security office.

Ken, I taught migrant farm wives sewing in Immokalee in the early 70’s. Also taught childbirth classes there and developed a program for pregnant teens. We lived at Corkscrew Swamp Sanctuary about 18 miles west. We left there in 1978. We visited there last November and were amazed at the size and conditions in Immokalee. Things were not as depressing as they were earlier. A good friend taught second grade there and would start the year with 6 kids, but by Christmasa her class would have 27 or more kids. She was dedicated to helping the children of migrants learn stayed there until she retired a couple of years ago. I enjoyed your photo essay of the faces of those farm workers.

I wanted to mention the contributions of Estella Mims Pyfrom, the CEO of Estella’s Brilliant Bus. Her family was featured in Harvest of Shame and in the Smithsonian Institute travelling exhibit, Field to Factory. This exhibit was curated by Dr. Spencer Crew and there is also a fine companion book by the same name. Her family story is also mentioned in a museum exhibit in the Belle Glade museum. I learned what the lives of migrant workers were like and I have such a deep understanding of what these invisible people went through–it is really important that this history be told. Another very excellent book that talks about this subject is “The Warmth of Other Suns by Isabel Wilkerson.

I spent many months out in South Florida’s farming community trying to document the lifestyles there. The Harvest of Shame and The Post’s Migration to Misery series was my inspiration.