I’ve noticed an unusual traffic bump on the stories I’ve done about Neely’s Landing and the horrific steamboat The Stonewall disaster that occurred in 1869. That prompted me to post an update that is more speculation than fact.

I’ve noticed an unusual traffic bump on the stories I’ve done about Neely’s Landing and the horrific steamboat The Stonewall disaster that occurred in 1869. That prompted me to post an update that is more speculation than fact.

Here’s a little refresher. You can go to my original post for more detail.

- Oct. 27, 1869, the steamboat The Stonewall, heavily laden with about 300 passengers, tons of cargo and 200 head of livestock was southbound on the Mississippi River near Neely’s Landing, bound for Cape Girardeau, Memphis and New Orleans. The river was low and the boat was running “slow wheel.”

- A candle or lantern overturned or a passenger dropped a spark onto hay on the lower deck, which caught fire. Before the blaze was discovered, it had gained considerable headway.

- The captain tried to beach the boat, but it struck a sandbar and turned in the wind and current until the flames fully engulfed the vessel. Nobody knows exactly how many people burned, drowned or died of exposure because the passenger list burned with the steamboat. Estimates place the toll between 209 to 300.

- Some 60 or 70 unidentified or unclaimed victims were buried in a mass grave on the Cotter Farm.

A hunt for the grave site

I spent quite a bit of time driving around Neely’s Landing searching for the grave site, but there’s not much left of what was once a thriving town. Mississippi River floods erased many buildings, much like they washed away Smelterville and Wittenberg. The Proctor & Gamble plant gobbled up even more of it.

I spent quite a bit of time driving around Neely’s Landing searching for the grave site, but there’s not much left of what was once a thriving town. Mississippi River floods erased many buildings, much like they washed away Smelterville and Wittenberg. The Proctor & Gamble plant gobbled up even more of it.

I thought a cemetery high on a hill overlooking the landing might be a possibility, but I quickly dismissed it.

Here’s why I didn’t think it qualified.

Here’s another possibility

Amateur historian Dick McClard and I started trading ideas. He has forgotten more about that area than I ever knew because of his research into the McClard family and its many offshoots.

Amateur historian Dick McClard and I started trading ideas. He has forgotten more about that area than I ever knew because of his research into the McClard family and its many offshoots.

He thought that the old Cotter Farm and grave site might be on Proctor and Gamble’s property in the general vicinity of the X. It was on the Neely’s Landing side of Indian Creek; the ground was fairly flat and the soil was soft.

Dick was a former P&G employee, so he knew the right ears to blow into to get us an escorted visit to our target area.

We struck out

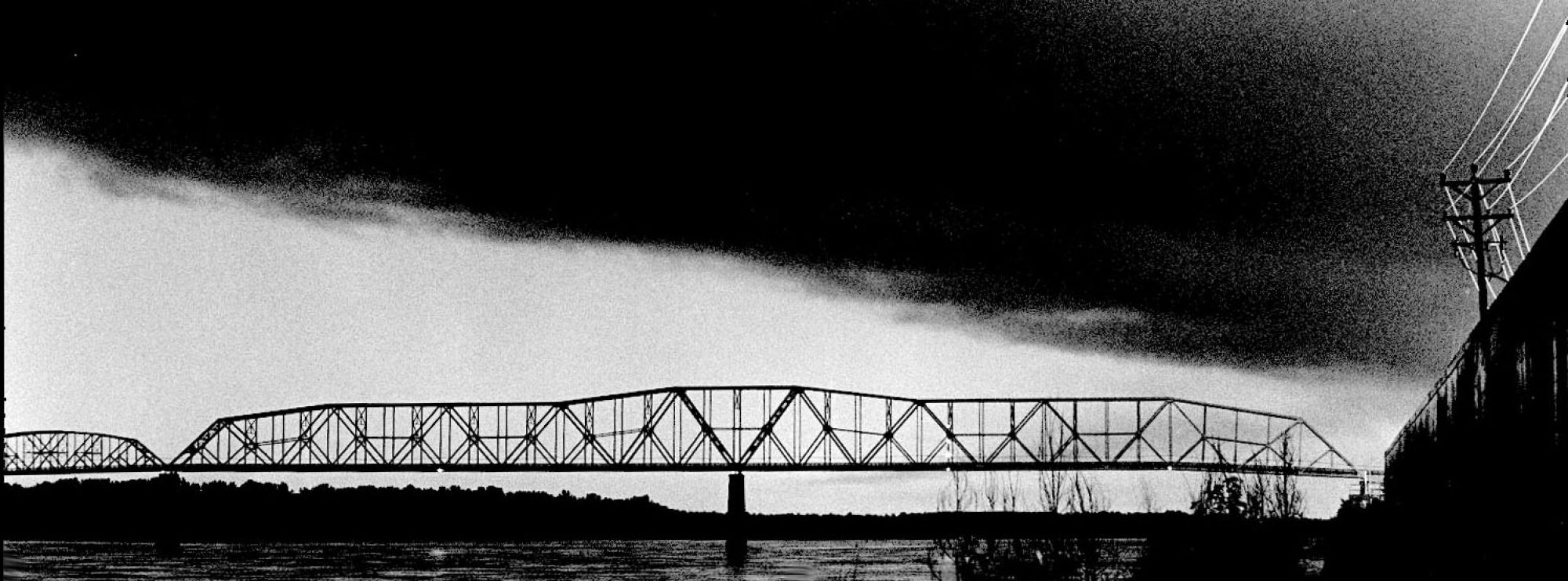

The security guard who was our ride and guide was on a tight schedule, so we didn’t get much time to nose around. I had time to shoot a nearly 360-degree panorama of the general area that didn’t show anything particularly interesting. The left side of the photo is looking north, then it swings to the right until we are looking approximately north-northwest.

The security guard who was our ride and guide was on a tight schedule, so we didn’t get much time to nose around. I had time to shoot a nearly 360-degree panorama of the general area that didn’t show anything particularly interesting. The left side of the photo is looking north, then it swings to the right until we are looking approximately north-northwest.

You’ll have to click on the photo to make it large enough to make out anything.

Dick thinks that any markers that might have existed were moved or covered over when the railroad cut through the area to carry visitors to the 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis. Decades of Mississippi River and Indian Creek floods probably scoured the area, plus it has been farmed.

We’re going to give it another shot, but timing is critical. It’ll help if we get there before the brush, snakes and bugs start showing up after wintertime. The best we can hope for would be some discarded stones or markers that have been pushed off to the edges of the property, but I doubt there was much around to set the graves off from the surrounding farmland.

Here’s one of the best accounts I’ve run across about the disaster and the history of the area.

Take a medal detector along, if people were buried in clothing, with medal clasps etc. You might get a hit, other than that, I see no way you could possibly find it with out more sophisticated equipment and digging.

Very interesting Ken. I’d never heard of this tragedy. Once again you’ve whetted my curiosity and I’ll have to research

Some interesting facts about river travel in the 1800’s

In 1847 the steamboats Talisman and Tempest collided near Cape; the Talisman sank, 51 people drowned. In January of 1848 the Sea Bird exploded on the Cape riverfront breaking out windows in the buildings; it was carrying gunpowder.

In October of 1886 the steamboat La Mascatte exploded due to pressure in it’s boilers near Neely’s Landing; 18 people died.

One might wonder why so many people lost their lives on the Stonewall; however, one must also understand that most people did not know how to swim in the 1800’s. Also, life preservers were likely not available to the passengers.

The Steamboat Act of 1871 had not been passed as of the time of the accident, which put into law several safety requirements. There were other acts including the 1838 Steamboat Act and the act of 1852, however, they were ineffective as they did not have inspection personnel to monitor compliance.

Another thought– if you look at Googlemaps and follow county road 525 as it goes south along Neely’s Landing, there is a slight bend & reverse bend in it as it goes along the railroad track appearing that they went around something. The question is why did they put a bend in the road unless they were going around something important? Also, they would have had to put the bodies on wagons to transport them and I doubt they would have made numerous trips if they could bury them close by conveniently. Lastly, assuming there was a service at the site for the families; I suspect they buried them by a road.I doubt they had the families walk through fields for a mile to get to the site??

The river “reach” around Cape Girardeau was known as “The Graveyard of Steam Boats” for the large number of boats that came to grief here.

Many ships were wrecked, blown up, burned, crushed by ice, and snagged.

As for explosions on steam boats, gun powder was not necessary.

One river boat’s boilers exploded up the river between Illinois and Iowa.

How violent these explosions were was illustrated when the purser was found in a corn field in Iowa and the mud clerk was found in a tree in Illinois.

One disaster happened in new Orleans when a fire started on one boat and spread to several others.

The young son of the Italian Consul was on one of the boats and was never found.

The Consul had a monument placed near the area showing his beloved son being lifted out of the flaming boat by an angel.

Samuel Clemens lost his brother to scalding in a boiler explosion just above Memphis.

A large number of people were killed and seriously injured.

Until WWII, the worst maritime disaster, river or ocean was the fire on a river boat way over loaded with Union soldiers who had been POW’s.

That “record” was broken when a Russian submarine torpedoed a German liner evacuating German soldiers and civilians trapped on the Baltic sea shore and about to be over run by Russian troops in early 1945.

I was told that it was at the foot of Dughill near the railroad crossing. It would be near the river & the road. By now, washed away long ago?

St. Louis Fire of 1849:

This fire was the largest and most destructive fire St. Louis has ever experienced. The fire lasted over 11 hours,and caused the loss of 5 lives, 430 buildings, 23 steamboats, 9 flat boats, and several barges.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/St._Louis_Fire_%281849%29

The St. Louis Fire of 1849 was a devastating fire that occurred on May 17, 1849 and destroyed a significant part of St. Louis, Missouri and many of the steamboats using the Mississippi River and Missouri River. This was the first fire in United States history in which it is known that a firefighter was killed in the line of duty. Captain Thomas B. Targee was killed while trying to blast a fire break.

In the spring of 1849, the population of St. Louis was about 63,000 with a western boundary of the city extending to 11th Street. The city was about three quarters of a mile in width and had about three miles of riverfront filled with steamboats and other river craft. St. Louis, located near the junction of the Mississippi and Missouri rivers, was the last major city where travelers could get supplies before they headed west. Here travelers bought supplies and switched steamboats before going up the Missouri River to Omaha, Nebraska or other trail heads for the Oregon and California trails west. At the time of this fire, the city was also experiencing a cholera epidemic which would end up killing about 10% of the population (over 4,500). The town was booming as people came in from around the U.S. and abroad and bought supplies before heading overland to participate in the California Gold Rush.

On May 17, 1849 at 9:00 p.m. a fire alarm sounded in St. Louis. The paddle wheeled steamboat “The White Cloud” on the river at the foot of Cherry Street was on fire. The volunteer Fire Department with nine hand engines and hose reel wagons promptly responded. The moorings holding the “White Cloud” burned through and the burning steamboat drifted slowly down the Mississippi River, setting 22 other steam boats and several flatboats and barges on fire.

The flames leaped from the burning steamboats to buildings on the shore and was soon burning everything on the waterfront levee for four blocks. The fire extended to Main Street westward and crossing Olive Street. It completely gutted the three blocks between Olive and 2nd Street and went as far south as Market Street. It then ignited a large copper shop three blocks away and burned out two more city blocks. The volunteer firemen, after laboring for eight hours, were nearly completely demoralized and exhausted. The entire business district of the city appeared doomed unless something was done. Six businesses in front of the fire were loaded with kegs of black powder and blown up in succession. Captain Thomas B. Targee of Missouri Company No. 5 died while he was spreading powder into Phillips Music store, the last store chosen to be blown up.

This fire was the largest and most destructive fire St. Louis has ever experienced. The fire lasted over 11 hours, from 9:00 p.m. until 8:00 a.m., and caused the loss of 3 lives, 430 buildings, 23 steamboats, 9 flat boats, and several barges. As a result of these fires, a new building code required new structures to be built of stone or brick and an extensive new water and sewage system was started.

Thanks Mr Brune! That was an interesting and most informative report.

An older map that I have shows a pre-existing cemetery where the mass grave may have been added to it. The stories about the cemetery describe the stones, not the graves, being moved and piled out of the way of a railroad bed being constructed. The cemetery was adjacent to the accident.

Sultana was the wreck carrying the union POWs from encampment in Fisk. I believe over 1500 people died in this steamboat accident on the mighty Mississippi. I’ve explored the neelys landing for many hours on different days, it’s very intriguing the history along those shores.

Can anyone tell me if this steamboat “Stonewall” is the same one owned (at least at one time) by Captain John Sterling Shaw of St. Charles, Missouri? Any info please email to anne.cloyd.cassens@gmail.com