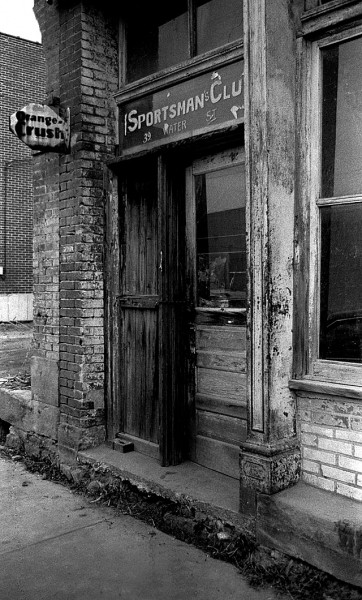

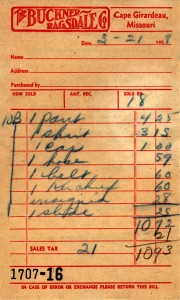

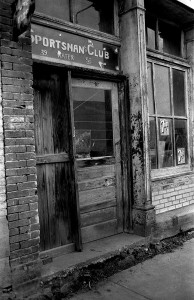

I shot the doorway to the Sportsman’s Club at 39 North Water Street when I was going through one of my periodic “peeling paint” phases. I didn’t know anything about the Sportsman’s Club, I just thought it was neat. It was probably shot around 1966.

I shot the doorway to the Sportsman’s Club at 39 North Water Street when I was going through one of my periodic “peeling paint” phases. I didn’t know anything about the Sportsman’s Club, I just thought it was neat. It was probably shot around 1966.

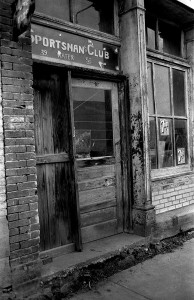

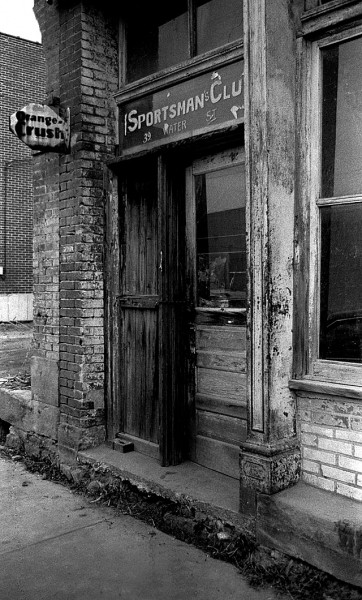

Sportsman’s Club in 2009?

When I went walking down Water Street in 2009, I carried a copy of the photo with me to see if I could shoot a before and after picture. I thought it looked like it had become the back entrance to Port Cape. The door post at the right looks the same, only in better condition; there are two courses of brick on the left side of the door and an open space with a foundation stone sticking out.

When I went walking down Water Street in 2009, I carried a copy of the photo with me to see if I could shoot a before and after picture. I thought it looked like it had become the back entrance to Port Cape. The door post at the right looks the same, only in better condition; there are two courses of brick on the left side of the door and an open space with a foundation stone sticking out.

39 North Water St. collapsed in 1968

I was surprised to run across an October 16, 1968, Missourian story that said the front part of the building at 39 North Water Street had collapsed. Workers for Gerhardt Construction said the two-story brick structure apparently caved in from the roof because of its old age.

I was surprised to run across an October 16, 1968, Missourian story that said the front part of the building at 39 North Water Street had collapsed. Workers for Gerhardt Construction said the two-story brick structure apparently caved in from the roof because of its old age.

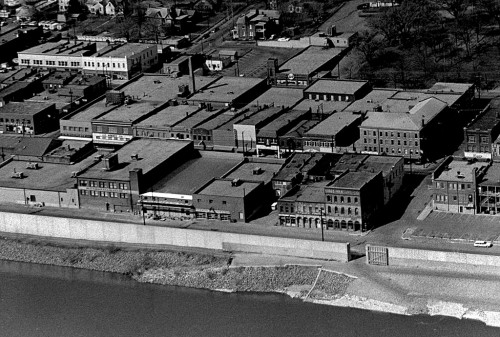

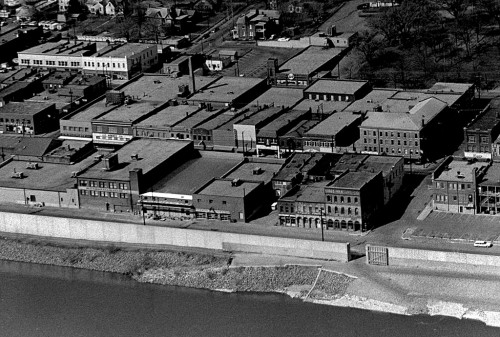

How could something collapse in 1968, but still be around in 2009? This aerial photo of that block, taken before 1968, shows the three-story building that became Port Cape on the right. To its left, next to the parking lot that looks like a missing tooth, is a two-story building with three windows. Sandwiched in the middle is a two-story building with five windows.

It sounds like the 39 Water Street building collapsed from the middle in, spilling some bricks into the street, but leaving at least the front wall partially intact. It must have been rebuilt as a one-story building.

Problems with “Negro” Sunday night dances

Harold Abernathy, Oscar Abernathy, Charles Wilson, Harry Lee and Maso Meacham, representing the Sportsman’s Club, 39 North Water, an organization seeking to help Negro teen-age youngsters, called on the city council, The Missourian reported Dec. 9, 1958, using distinctions that signal how segregated the city was going into the 60s.

Harold Abernathy, Oscar Abernathy, Charles Wilson, Harry Lee and Maso Meacham, representing the Sportsman’s Club, 39 North Water, an organization seeking to help Negro teen-age youngsters, called on the city council, The Missourian reported Dec. 9, 1958, using distinctions that signal how segregated the city was going into the 60s.

A Sunday night dance sponsored by the group was halted when there was a complaint. The council explained that city ordinance prohibits public dances on Sunday. If the organization was private, the said, did not sell tickets and held a party as a private organization, that was another matter.

The visitors said it was a private group designed to raise funds to provide recreation for teen-age Negro youths. Programs for the youths are held on Friday nights during the school year and on Tuesday and Friday in the summer, they said.

Caught fire in 1939

Cape’s downtown was threatened by fire when three business buildings caught fire, The Missourian reported Feb. 27, 1939. The blaze started on the second floor and involved the Co-op drug store, Fred Bark’s cafe, the Louis Suedekum cafe and beer parlor and a rooming house entrance on the Main Street side. On the Water Street side, were the Charles Young and Ben Edwards Negro cafes.

Cape’s downtown was threatened by fire when three business buildings caught fire, The Missourian reported Feb. 27, 1939. The blaze started on the second floor and involved the Co-op drug store, Fred Bark’s cafe, the Louis Suedekum cafe and beer parlor and a rooming house entrance on the Main Street side. On the Water Street side, were the Charles Young and Ben Edwards Negro cafes.

The paper said the fire apparently started on one of the Young Negro rooming houses, how or exactly where hadn’t been determined at the time of the writing.

Mr. and Mrs. Barks, who lived above their cafe, were momentarily trapped there. Mr. Barks, who hadn’t been feeling well, was in bed. Mrs. Barks rushed upstairs, using a rear stairway, then on fire, to call him. This was the only exit, and it was shut off by fire and smoke before they could escape. Firemen had to place a ladder on the front of the building to get them to safety.

The third floor of the Young building was mostly gutted and some damage was done to the second floor. Since the aerial shows that it was only two stories in the middle 60s, I’m guessing that the building lost its third story during its repair.

Here’s a semi-mystery. The negative sleeve just had a date – March 27, 1967 – written on the front of it. The setting is Main Street, but I don’t know why the two photos were taken. There’s a huge gap in the Google News Archive for the month of March 1967, so I couldn’t even search for them there.

Here’s a semi-mystery. The negative sleeve just had a date – March 27, 1967 – written on the front of it. The setting is Main Street, but I don’t know why the two photos were taken. There’s a huge gap in the Google News Archive for the month of March 1967, so I couldn’t even search for them there. If the sign on Cape Federal is correct, the photo was taken at 4:08 in the afternoon on a day that was chilly, but not cold and windy enough to really bundle up.

If the sign on Cape Federal is correct, the photo was taken at 4:08 in the afternoon on a day that was chilly, but not cold and windy enough to really bundle up.