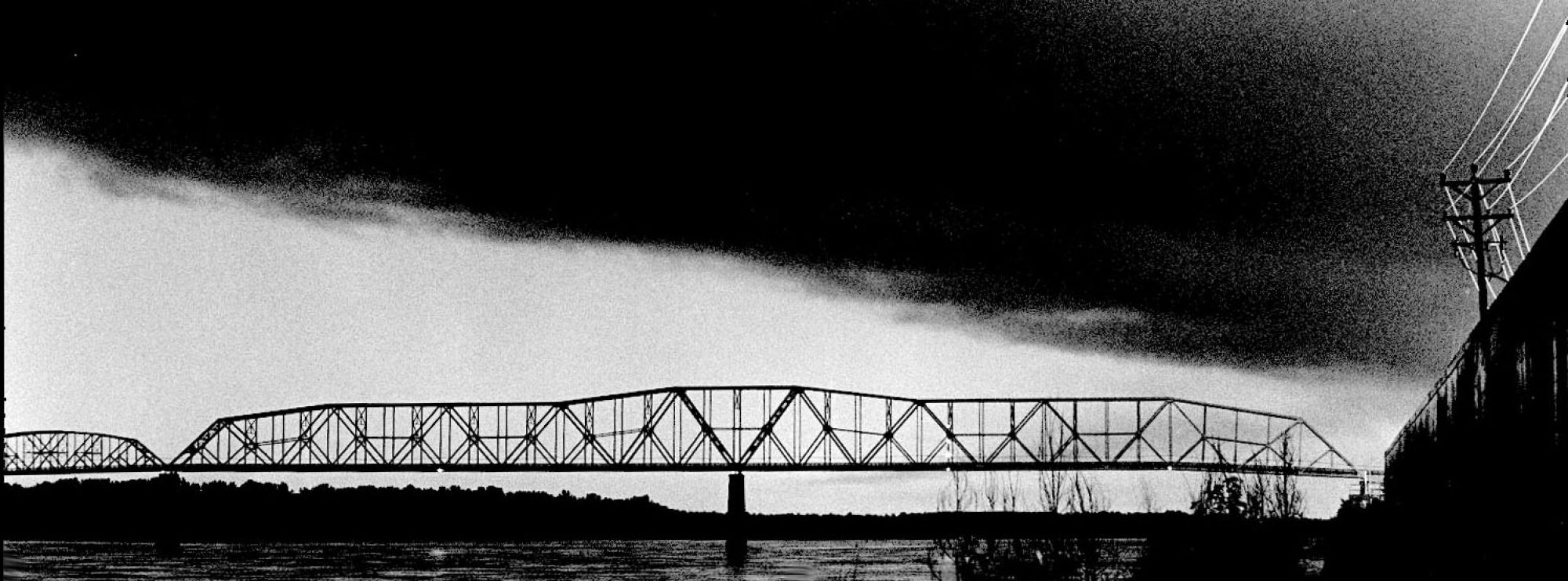

Whenever I spot a towboat in one of my pictures, I try to blow it up large enough to read the name. The Issaquena, 170 feet long and 40 feet wide, was built in 1966 by Jeffboat, Inc., in Jeffersonville, Ind.

Whenever I spot a towboat in one of my pictures, I try to blow it up large enough to read the name. The Issaquena, 170 feet long and 40 feet wide, was built in 1966 by Jeffboat, Inc., in Jeffersonville, Ind.

A Google search turned up two lawsuits the vessel was involved in. They are interesting because they give insight into the job of a deckhand and the intricacies of navigating the river.

Zachary Killebres

You can read Security Barge Line vs. Zachary Killebrew here.

Zachary Killebrew was a deckhand who was tasked with stringing a light cord to the leading barge so it would have a starboard and port light. Instead of walking approximately 100 feet to a ladder on the tow knee, he elected to jump from an empty barge to a loaded barge, a distance of about 2 feet down and 1-1/2 feet out. He said he experienced a sharp pain in his back when he landed and sued the boat’s owners, Security Barge Line., Inc.

The deckhand based his claim for damages on “the unseaworthiness of the towboat and its barges and the negligence of the appellant, in failing to furnish appellee with a safe place to work, failure to properly instruct the appellee in the course of his duties and failure to warn the appellee of the dangers incident to his work.”

The counter argument was that the Issaquena WAS seaworthy in the sense that it was “reasonably suitable for her intended service….The standard is not perfection, but reasonable fitness; not a ship that will weather every conceivable storm or withstand every imaginable peril of the sea.”

As far as the argument that Killebrew wasn’t properly instructed: “Rather than walk the additional 100 feet, he suddenly and on his own decided to jump. He could have sat down and extended his feet over to the coaming, or he could have held on to the edge of the empty and dropped to the deck of the loaded barge. He could have simply stepped across because the coaming was only 1 1/2 feet away. If there were any danger in jumping, it was perfectly obvious to any person of average or reasonable intelligence. It was not a danger peculiar to ships or barges. A workman putting a roof on a long chickenhouse, rather than use a ladder some distance away, could suddenly decide to jump from the roof to the ground. An employer is under no duty to instruct an employee that in performing his work he should not jump from a greater height to a lower height. A person of even everyday common garden variety of intelligence just instinctively knows that he is taking some risk when he elects to jump from one level to another.”

A jury awarded the deckhand $60,000. After some legal wrangling, it was reduced $35,000.

L.W. Sweet collision

The Mississippi looks wide, but it’s possible to run out of river if two towboats try to navigate a narrow passage at the same time. Even in legalese, the account of a bump-up between the LW. Sweet and the Issaquena in 1971 paints a riveting picture of how things haven’t changed all that much since the days of Mark Twain.

Short version: the L.W. Sweet, lightly loaded with four empty barges and only 648 feet long, was southbound behind the Issaquena, which was heavily loaded with 25 loaded dry-bulk cargo hopper barges and was about 1,145 long and 175 feet wide. At about 1 a.m., the two vessels and some others were coming up on a tricky crossing below the Cherokee Light off the Bootheel. The crossing starts off wide, then narrows toward the bottom. The shorter L.W. Sweet could have made it with ease, but the longer Issaquena couldn’t steer the bends in one maneuver and would have to do some flanking maneuvers that would block the entire channel.

L.W. Sweet’s Captain Crutchfield, an experienced riverman, radioed the leading Issaquena to set up a passing agreement. Captain Harrrington, on the Issaquena, said that he “had the hole stopped up” and didn’t believe the L.W. Sweet could effect a safe passage, but he was willing to let Crutchfield “come on” if he thought he could make it.

The maneuver failed, the boats collided and the tows were broken. The trial judge ruled both captains were at fault: the L.W. Sweet’s because he attempted an unsafe maneuver and the Issaquena’s because he didn’t deny the request of the following boat to pass. Here’s an account of the appeal. I’ll leave it to a legal beagle like Bill Hopkins to interpret the findings.

The L.W. Sweet had been involved in a collision in 1959, but the fault was the other vessel’s. The L.W. Sweet was built in 1950.

Pretty interesting what you can find out about those boats passing you by.

These are a present to the SEMO student working on the Main Street Project who drew the St. Charles Hotel as a subject.

These are a present to the SEMO student working on the Main Street Project who drew the St. Charles Hotel as a subject. I tried to read the painted sign on the building south of the hotel, but I can’t quite make it out. It might be Sherman’s.

I tried to read the painted sign on the building south of the hotel, but I can’t quite make it out. It might be Sherman’s. The building that replaced the hotel was Sterling Variety Store, and it’s listed at 41 North Main.

The building that replaced the hotel was Sterling Variety Store, and it’s listed at 41 North Main. I took this picture of the St. Charles waiting for the wrecking ball on March 11, 1967. You can see more photos and read some history of the hotel here.

I took this picture of the St. Charles waiting for the wrecking ball on March 11, 1967. You can see more photos and read some history of the hotel here.