Hanging around cop shops was a good way get to know the men and women with badges before you ran into them as strangers at a spot news scene where confrontations could escalate. Besides, it was always fun to exchange war stories.

Hanging around cop shops was a good way get to know the men and women with badges before you ran into them as strangers at a spot news scene where confrontations could escalate. Besides, it was always fun to exchange war stories.

Dispatchers, in particular, could be your best friend. They could sometimes both follow the letter of their orders and still be helpful. “The captain said if you called to tell you that there is nothing going on at 101 Main Street. Got that?” I spent a lot of time at the Cape County Sheriff’s office in Jackson. Part of that was because it was across the courthouse square from The Jackson Pioneer, and partly because Deputy Jon Knehans and I became friends while taking some SEMO classes together.

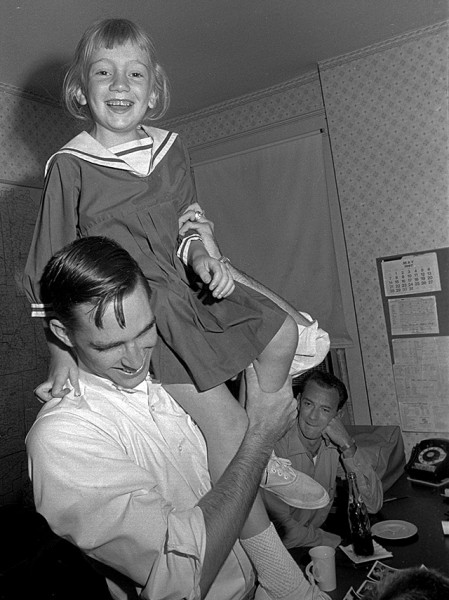

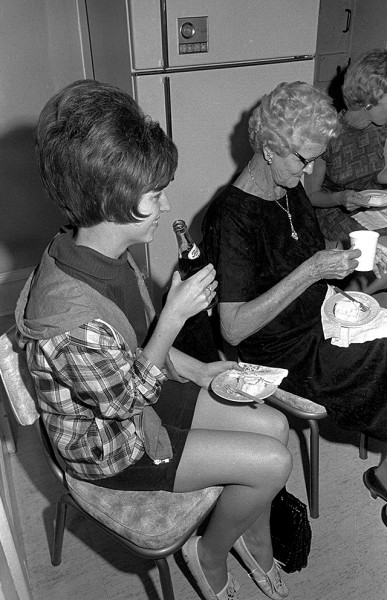

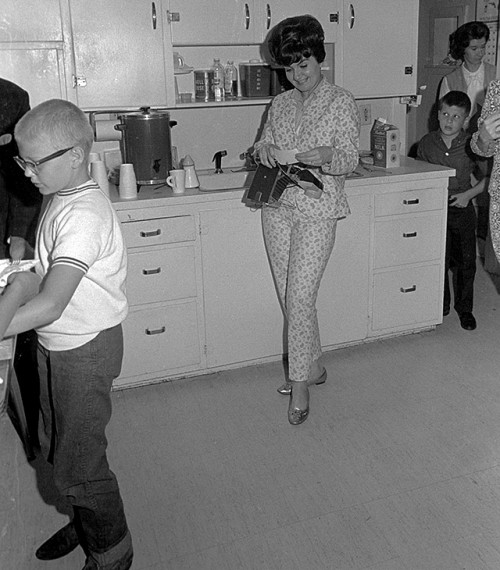

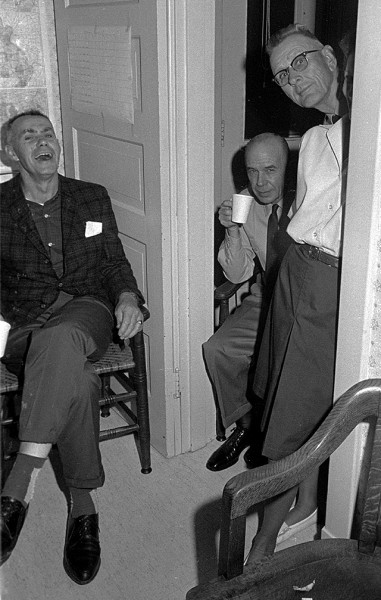

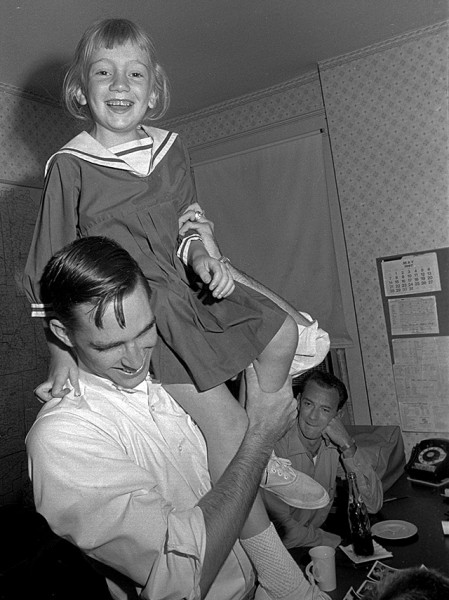

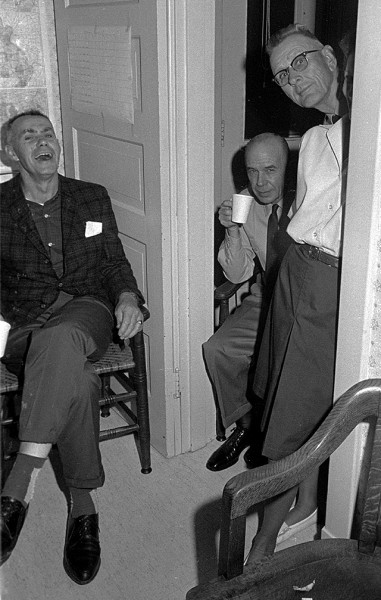

That might have been why I was around when Sheriff Ivan McLain was the target of a surprise birthday party. None of these photos ran in The Missourian, so I was either tipped off about the party or I just happened to be lurking there.

Always a nice guy

The sheriff showed extraordinary patience to a green reporter. He always took the time to answer my questions and never, so far as I knew, lied to me. I photographed him on a number of occasions, including demonstrating lie detectors techniques to students.

The sheriff showed extraordinary patience to a green reporter. He always took the time to answer my questions and never, so far as I knew, lied to me. I photographed him on a number of occasions, including demonstrating lie detectors techniques to students.

Jon Knehans for sure

I recognize some of the faces in the pictures, but Jon is the only one I can ID for sure.

I recognize some of the faces in the pictures, but Jon is the only one I can ID for sure.

Ivan McLain died Feb. 22, 2013

I was sorry to find his obituary in The Missourian.

I was sorry to find his obituary in The Missourian.

Ivan Ernest McLain, 82, of Cape Girardeau died Friday, Feb. 22, 2013, at Saint Francis Medical Center. He was born June 1, 1930, in Oriole to Monroe and Myrtle Comer McLain.

Ivan was a veteran of the Korean War, serving in the Navy. He and Betty Lois Jauch were married June 19, 1954, at Oriole.

Sheriff from 1966 to 1977

Mr. McLain worked for the Cape Girardeau Police Department from September 1955 to November 1966 and was sheriff of Cape Girardeau County from November 1966 to January 1977. He was in real estate sales from 1977 to 1980 and worked at the Gene Rhodes Oil Co. from 1980 to 1983.

Mr. McLain worked for the Cape Girardeau Police Department from September 1955 to November 1966 and was sheriff of Cape Girardeau County from November 1966 to January 1977. He was in real estate sales from 1977 to 1980 and worked at the Gene Rhodes Oil Co. from 1980 to 1983.

Ivan was chief of police in Chaffee, Mo., from 1983 to 1992. He retired from Wal-Mart after being a greeter from June 1992 to December 2010.

A member of VFW

He was a member of the Cape County Cowboy Church and attended Red Star Baptist Church. He also was a member of the VFW Post 3127 in Chaffee.

Survivors

Survivors include his wife, Betty Lois McLain of Cape Girardeau; sons Ivan (Aida) Santos of Grand Prairie, Texas, and Randy (Judy) McLain of Cape Girardeau; daughters Cathy Proffer of Advance, Mo., and Penny (Curt) Johns of Jackson; a brother, Jack (Jean) McLain of Cape Girardeau; sisters, Carrie Wilhelm of Mount Dora, Fla., and Mary Wissmann of Cape Girardeau; nine grandchildren; and six great-grandchildren.

Survivors include his wife, Betty Lois McLain of Cape Girardeau; sons Ivan (Aida) Santos of Grand Prairie, Texas, and Randy (Judy) McLain of Cape Girardeau; daughters Cathy Proffer of Advance, Mo., and Penny (Curt) Johns of Jackson; a brother, Jack (Jean) McLain of Cape Girardeau; sisters, Carrie Wilhelm of Mount Dora, Fla., and Mary Wissmann of Cape Girardeau; nine grandchildren; and six great-grandchildren.

He was preceded in death by his parents, seven brothers, two sisters and two grandsons, Rusty Watson and Colin McLain.

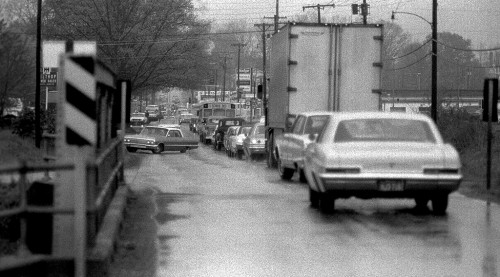

Yes, children, we had traffic jams in Cape in The Old Days. I shot this one on Independence looking toward Kingshighway on the same day I shot the demolition of the St. Charles Hotel, April 13, 1967.

Yes, children, we had traffic jams in Cape in The Old Days. I shot this one on Independence looking toward Kingshighway on the same day I shot the demolition of the St. Charles Hotel, April 13, 1967.