I was alone walking around in St. Mary’s Cemetery looking at graves of servicemen Friday afternoon. I was looking for a specific grave, but didn’t run across it.

I was alone walking around in St. Mary’s Cemetery looking at graves of servicemen Friday afternoon. I was looking for a specific grave, but didn’t run across it.

What I did find in just about a third of the graveyard was the final resting place of many men who served in our country’s various conflicts, then came back to rejoin their community. Look at how many bronze markers are catching the late afternoon sun. You can click on the photos to make them larger. Here are just a few of the markers and the men they represent.

An obituary in The Southeast Missourian on Sept. 30, 1980, said that Adolph C. Halter had served in the Army in Europe. He worked as a mechanic at Ford Groves Motor Company until he retired due to ill health.

James Patrick “Pat” Tlapek

James “Pat” Tlapek earned a long obit in the June 28, 2016, Missourian. It was interesting that his military past didn’t even get a mention, maybe because he had accomplished so many other things in his life.

James “Pat” Tlapek earned a long obit in the June 28, 2016, Missourian. It was interesting that his military past didn’t even get a mention, maybe because he had accomplished so many other things in his life.

[He] “took a small auto-parts store in Cape Girardeau and watched it grow into business that spans four states. He also contributed to the community through time and donations throughout his life. Tlapek bought Auto Tire and Parts in 1948, when it was one store in Cape Girardeau. Over the years, he expanded, opening a store in Sikeston, Missouri, then adding a parts warehouse. He sold the business to his son John Tlapek in the 1980s, but he remained involved in the company. It has grown to 49 stores in four states with more than 300 employees.”

Paul Scherer Sr.

A March 14, 2012, Missourian obituary said that Paul Scherer Sr., was born in Advance in 1920, and served in the Army Air Corps during World War II. It reported that he was production manager at Davis Electric, worked as a carpenter, and was an avid gardener.

A March 14, 2012, Missourian obituary said that Paul Scherer Sr., was born in Advance in 1920, and served in the Army Air Corps during World War II. It reported that he was production manager at Davis Electric, worked as a carpenter, and was an avid gardener.

John W. Byrne

The Dec. 31, 1981, obit said that John W. Byrne came to Cape Girardeau with the Phillips Petroleum Co., and later became assistant administrator at St. Francis Medical Center. He moved to Jefferson City in 1975, and became medical services coordinator for the Missouri Department of Corrections.

The Dec. 31, 1981, obit said that John W. Byrne came to Cape Girardeau with the Phillips Petroleum Co., and later became assistant administrator at St. Francis Medical Center. He moved to Jefferson City in 1975, and became medical services coordinator for the Missouri Department of Corrections.

Freeman E. Moyers

Freeman Eugene “Gene” Moyers, served in the Air Force during both the Korean and Vietnam wars. After he retired as a master sergeant in 1970, he worked for the Missouri Department of Natural Resources. He was superintendent of Trail of Tears State Park for three years.

Freeman Eugene “Gene” Moyers, served in the Air Force during both the Korean and Vietnam wars. After he retired as a master sergeant in 1970, he worked for the Missouri Department of Natural Resources. He was superintendent of Trail of Tears State Park for three years.

Leon Jansen

Leon Jansen served aboard a Coast Guard patrol frigate during World War II. When he returned home, worked for Midwest Dairy. In 1959, he started B&J Refrigeration. He established Jaymac Equipment in 1963, which was one of the longest-established Carrier dealers in the country.

Leon Jansen served aboard a Coast Guard patrol frigate during World War II. When he returned home, worked for Midwest Dairy. In 1959, he started B&J Refrigeration. He established Jaymac Equipment in 1963, which was one of the longest-established Carrier dealers in the country.

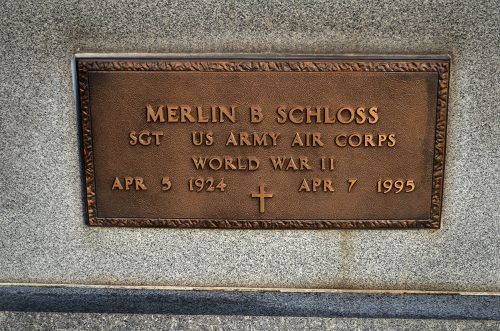

Merlin B. “Bud” Schloss

Merlin B. Schloss served with the Air Force in England, France and Germany from 1943 to 1946. Mr. Schloss worked as a route salesman for Locke Distributing for 25 years, then for Bluff City Beer, until he retired in 1977. He worked part-time for Bi-State Southern Oil Co. after retiring.

Merlin B. Schloss served with the Air Force in England, France and Germany from 1943 to 1946. Mr. Schloss worked as a route salesman for Locke Distributing for 25 years, then for Bluff City Beer, until he retired in 1977. He worked part-time for Bi-State Southern Oil Co. after retiring.

John W. Dean

John W. Dean, spent 18 years with the Army Nurse Corps, served in both Korea and Vietnam, and retired with the rank of major. He was director of nursing at St. Francis Medical Center for two years, then opened the Sub and Suds in 1978.

John W. Dean, spent 18 years with the Army Nurse Corps, served in both Korea and Vietnam, and retired with the rank of major. He was director of nursing at St. Francis Medical Center for two years, then opened the Sub and Suds in 1978.

Raymond C. Seyer

I had to pause a few extra minutes in front of Ray Seyer’s stone. I didn’t have to look up his obituary. I knew him as Wife Lila’s favorite uncle. He was the consummate storyteller. I wrote at the time of his death, “You could tell when Ray was going to let loose with a good one by the way he’d get this half-grin with his lower lip pooched out just a little bit; then the crinkles would show up in the corners of his eyes. That’s a sign of a man who has laughed well and often.”

I had to pause a few extra minutes in front of Ray Seyer’s stone. I didn’t have to look up his obituary. I knew him as Wife Lila’s favorite uncle. He was the consummate storyteller. I wrote at the time of his death, “You could tell when Ray was going to let loose with a good one by the way he’d get this half-grin with his lower lip pooched out just a little bit; then the crinkles would show up in the corners of his eyes. That’s a sign of a man who has laughed well and often.”

I had the pleasure of spending an afternoon with Lila, Ray, Mother, and Aunt Rose Mary. I had the foresight to keep a video camera running while Ray was talking about growing up in Swampeast Missouri, serving in the Navy and developing a low opinion of Rush Limbaugh. You can find them at this link.