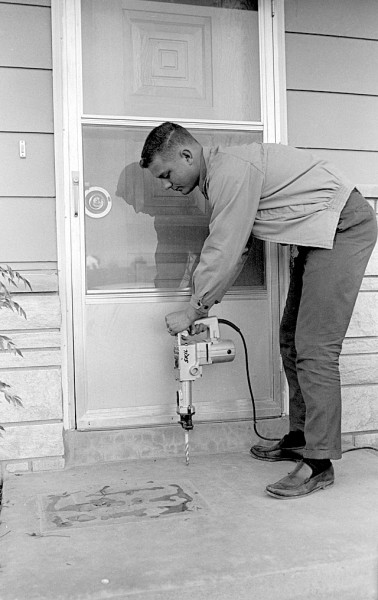

These photos were taken for a freelance job for General Pest Control. I don’t know if they were for a brochure, a Missourian ad or what. I also don’t know the names of the people in the photo. They were probably shot around 1964. Click on any photo to make it larger.

These photos were taken for a freelance job for General Pest Control. I don’t know if they were for a brochure, a Missourian ad or what. I also don’t know the names of the people in the photo. They were probably shot around 1964. Click on any photo to make it larger.

Checking under the sink

The lady of the house must have known we were coming because I don’t think I’ve ever seen an area under a kitchen sink so neat and organized.

The lady of the house must have known we were coming because I don’t think I’ve ever seen an area under a kitchen sink so neat and organized.

I took my flash off the camera, but I should have bounced it off the ceiling to get rid of the harsh shadow behind the guy’s head. Maybe I thought about doing that but was afraid it wouldn’t get enough light under the sink. That’s one advantage of today’s digital cameras: you can see the picture before you leave.

Shadow shows Honeywell strobe

I would never have made a print that showed my shadow or any sign of me, but I left my shadow in here because it shows the Honeywell Strobonar 65C or 65D strobe bolted on the camera. I had both over the years They were called “potato mashers” because of their shape. The 65C used rechargeable batteries in the head. The disadvantage was that it was slow to recycle, so you couldn’t shoot one shot right after another.

I would never have made a print that showed my shadow or any sign of me, but I left my shadow in here because it shows the Honeywell Strobonar 65C or 65D strobe bolted on the camera. I had both over the years They were called “potato mashers” because of their shape. The 65C used rechargeable batteries in the head. The disadvantage was that it was slow to recycle, so you couldn’t shoot one shot right after another.

The 65D used a 510-volt battery that dangled from a case on your belt. It recycled quickly because of the high voltage zap it gave the capacitors. Since it used the same frame as the 65C and because it didn’t use batteries in the head, there was a neat little storage space where you could put a spare cord or other accessory.

The high-voltage battery had one drawback (other than being relatively expensive): if the battery cord had a short and you were anywhere near a wet surface, all that voltage would surge though YOU and flat put you on the ground. I was walking across a wet football field one night when I thought I had been tackled from behind. After a second jolt, I decided it was time to go back to the car for a spare cord.

What channel were they watching?

Here’s another shot I would have cropped tighter in the real world, but I left it wide so you could speculate what TV channel they were watching. Their antenna is pointing to the northwest. I would have thought the KFVS World’s Tallest Man-made Structure would have been more to the north toward Egypt Mills. The only two other stations you could pick up in Cape were Paducah to the north-northeast and St. Louis to the north.

Here’s another shot I would have cropped tighter in the real world, but I left it wide so you could speculate what TV channel they were watching. Their antenna is pointing to the northwest. I would have thought the KFVS World’s Tallest Man-made Structure would have been more to the north toward Egypt Mills. The only two other stations you could pick up in Cape were Paducah to the north-northeast and St. Louis to the north.

That would have been about the right direction to pick up the old KFVS tower that was located next to North County Park near the old KFVS radio tower, but by the mid-60s when these photos were taken that tower wasn’t used any more.

[Wife Lila, who was proofreading this, thinks it was Harrisburg we watched instead of St. Louis. The channels she remembers getting were 3, 6 and 12. I’m certainly not going to contradict her.]

Owned and operated by the Paynes

Leeman Payne’s obituary in the Dec. 29, 2010, Missourian said that Mr. Payne and his wife, Dorothy, owned and operated General Pest Control for 35 years. He also built and sold homes in Cape and Bollinger counties. I didn’t make a personal connection with General Pest Control until I saw that Mr. Payne was survived by a daughter, Carolyn. In the interest of full disclosure, Carolyn and I dated briefly before I won a coin toss with Jim Stone and hooked up with the future Wife Lila. Maybe that’s how I got the freelance job.

Leeman Payne’s obituary in the Dec. 29, 2010, Missourian said that Mr. Payne and his wife, Dorothy, owned and operated General Pest Control for 35 years. He also built and sold homes in Cape and Bollinger counties. I didn’t make a personal connection with General Pest Control until I saw that Mr. Payne was survived by a daughter, Carolyn. In the interest of full disclosure, Carolyn and I dated briefly before I won a coin toss with Jim Stone and hooked up with the future Wife Lila. Maybe that’s how I got the freelance job.

An Internet search landed me on the D & L Pest Control website where it says that in 1987 “D&L makes its largest acquisition to date by purchasing General Pest Control Company of Cape Girardeau MO. With this purchase D&L opens its first branch office, in Cape Girardeau. After years of steady growth in the Dexter office this merger makes D&L the largest pest control company in Southeast Missouri. By now the D&L team has grown from 1 employee in 1979 to 14 employees. Greg DeProw now takes over as branch manager in the Cape Girardeau office. The purchase of General Pest Control also introduces D&L service to southern Illinois.”