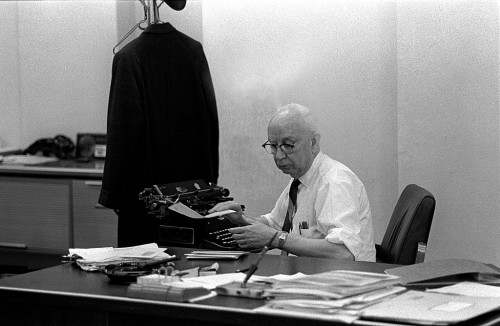

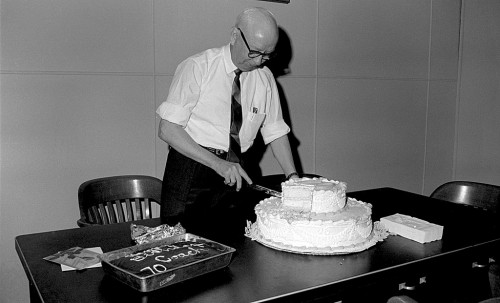

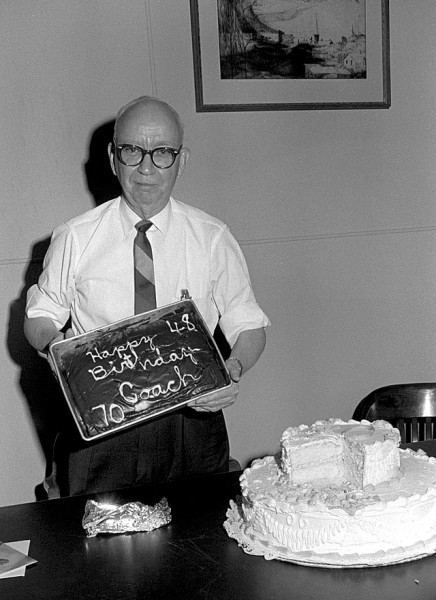

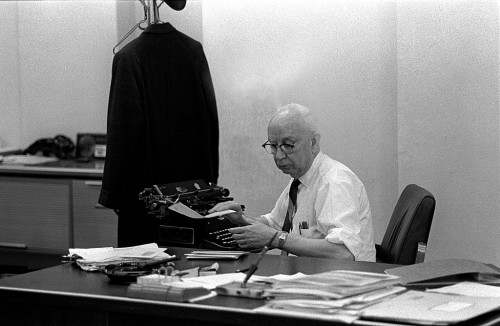

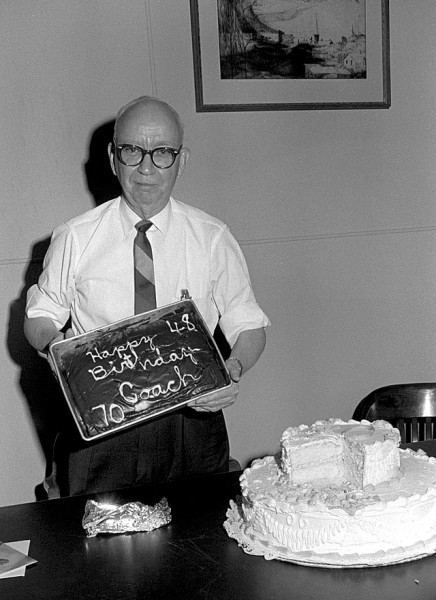

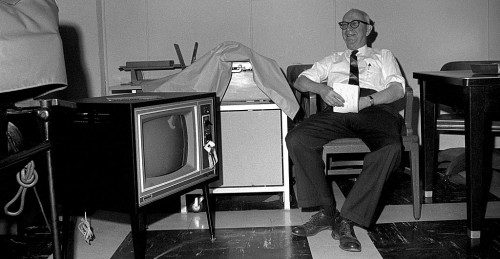

I was told to grab a camera and go downstairs to the business office to shoot some photos of Missourian Accountant S.P. Neal celebrating his 70th birthday and the anniversary of 48 years with the newspaper. Two of my photos of the celebration ran on the front page of the paper, but this picture I shot with a little half-frame camera on a lark one day when I was walking through the office captured more of the essence of the man.

I was told to grab a camera and go downstairs to the business office to shoot some photos of Missourian Accountant S.P. Neal celebrating his 70th birthday and the anniversary of 48 years with the newspaper. Two of my photos of the celebration ran on the front page of the paper, but this picture I shot with a little half-frame camera on a lark one day when I was walking through the office captured more of the essence of the man.

Minimal contact with accounting

I had minimal contact with the folks in the accounting department. From time to time, though, one of the staff would be dispatched up to the newsroom to beg me to deposit my paychecks so they could balance the books.

I had minimal contact with the folks in the accounting department. From time to time, though, one of the staff would be dispatched up to the newsroom to beg me to deposit my paychecks so they could balance the books.

See, even though I was only making $50 a week, plus another $20 or $25 in freelance photo money, I didn’t have all that many expenses. I lived at home, so about all I needed to survive was a little cash for gas and photo supplies. You could get a pizza for about three bucks and Lila worked at the Rialto, so movies were free.

I had more money left over on Missourian pay days than when I was making 20 times that in later years.

Newspapers offered lifetime employment

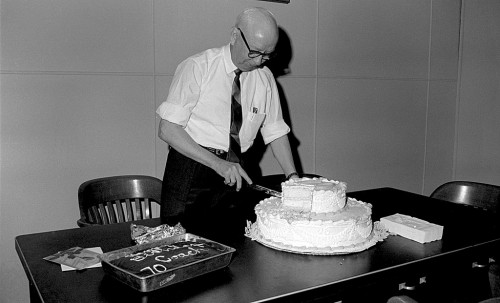

Mr. Neal started working for The Missourian in 1918, right out of business college. The paper itself was only 14 years old. His 70th birthday coincided with his 48th year with the paper. I searched for his obituary, but couldn’t find it so see how many more years he worked. [See update below.]

Mr. Neal started working for The Missourian in 1918, right out of business college. The paper itself was only 14 years old. His 70th birthday coincided with his 48th year with the paper. I searched for his obituary, but couldn’t find it so see how many more years he worked. [See update below.]

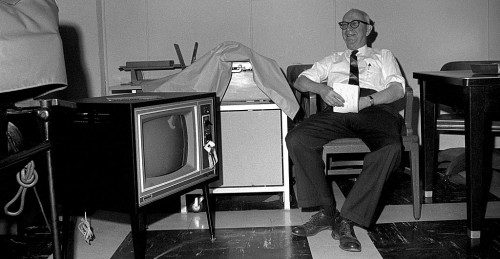

Given color TV

The paper and his coworkers chipped in to buy him a color television set. That was a little funny, because it was newsroom style to pretend, as much as possible, that radio and TV didn’t exist. We would refer to “a local television station,” even though there was only one.

The paper and his coworkers chipped in to buy him a color television set. That was a little funny, because it was newsroom style to pretend, as much as possible, that radio and TV didn’t exist. We would refer to “a local television station,” even though there was only one.

Bean counter AND cartoonist

In addition to his math duties, Mr. Neal served as the paper’s cartoonist in the 1930s. He picked up the nickname “Coach” about the same time. He thinks it might have been because the Central High School football team had defeated a Paducah, Ky., team through the use of a strange play which Mr. Neal illustrated in The Missourian.

In addition to his math duties, Mr. Neal served as the paper’s cartoonist in the 1930s. He picked up the nickname “Coach” about the same time. He thinks it might have been because the Central High School football team had defeated a Paducah, Ky., team through the use of a strange play which Mr. Neal illustrated in The Missourian.

A man you call Mister

Mr. Neal was one of those old-time, classy guys who made working at newspapers special. You may have noticed that I usually refer to folks by either their first or last names in this blog. S. P. Neal was one of those folks who earned the “Mr.”

Mr. Neal was one of those old-time, classy guys who made working at newspapers special. You may have noticed that I usually refer to folks by either their first or last names in this blog. S. P. Neal was one of those folks who earned the “Mr.”

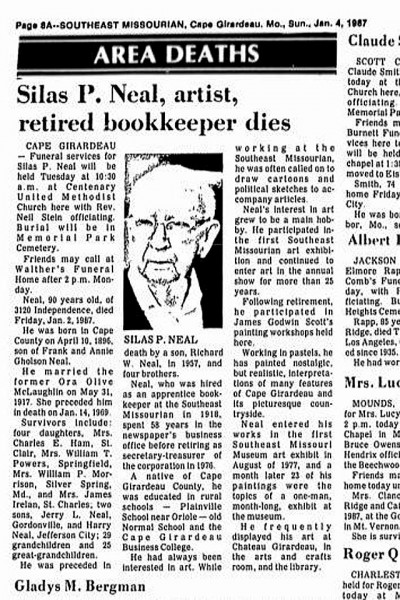

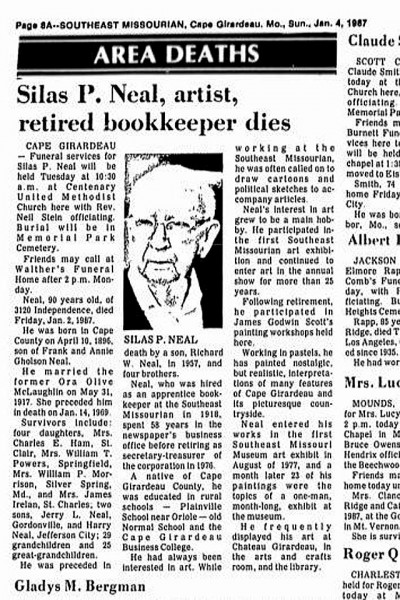

S. P. Neal Obituary

My friend, Shy Reader, is better at searching than I am. She sent me a copy of Mr. Neal’s obit. He went on to work another 10 years, retiring as secretary-treasurer in 1976. He died Jan. 2, 1987, at the age of 90.

My friend, Shy Reader, is better at searching than I am. She sent me a copy of Mr. Neal’s obit. He went on to work another 10 years, retiring as secretary-treasurer in 1976. He died Jan. 2, 1987, at the age of 90.

I see in The Missourian that the city is going to pull the plug on the Capaha Park swimming pool, literally. While rooting around trying to find pool pictures, I ran across these kids picking the lagoon instead of the pool.

I see in The Missourian that the city is going to pull the plug on the Capaha Park swimming pool, literally. While rooting around trying to find pool pictures, I ran across these kids picking the lagoon instead of the pool. I’m still digging for those pool photos. I know I’ve got the stuff from the Millie the Duck series, Lila’s synchronized swimming team, swimming classes, swim meets and diving competition. Be patient.

I’m still digging for those pool photos. I know I’ve got the stuff from the Millie the Duck series, Lila’s synchronized swimming team, swimming classes, swim meets and diving competition. Be patient.