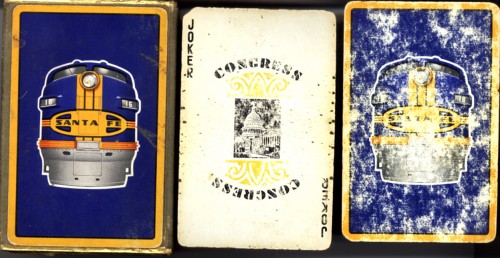

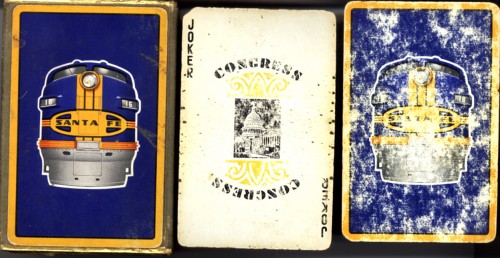

When I was 14, Bill Hardwick, Martin Dubs and I got on a train in Cape Girardeau that took us all to way out to Philmont Scout in New Mexico. While we were aboard the Santa Fe, I picked up this deck of cards to while away the time. It’s been living in a drawer with a bunch of other decks for 35 or 40 years.

When I was 14, Bill Hardwick, Martin Dubs and I got on a train in Cape Girardeau that took us all to way out to Philmont Scout in New Mexico. While we were aboard the Santa Fe, I picked up this deck of cards to while away the time. It’s been living in a drawer with a bunch of other decks for 35 or 40 years.

She’s a little worse for the wear, but the box still looks almost like new. I thought using Congress as the Joker might be a political commentary, but I found that it was the name of the card company.

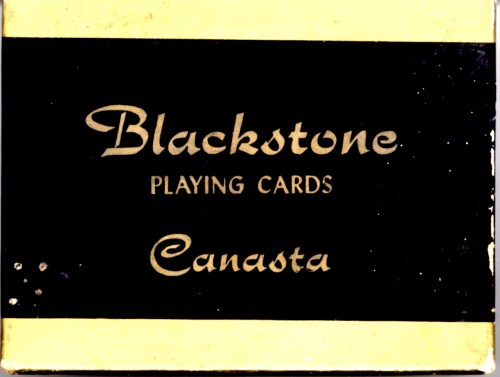

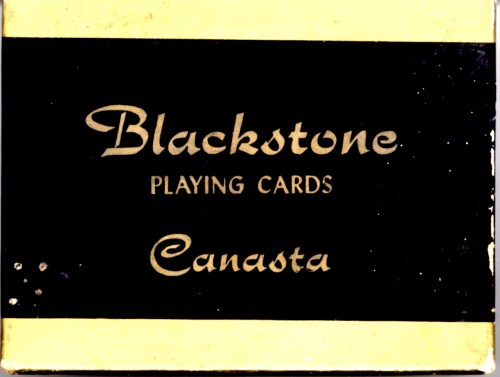

Dad and I played Canasta

When I wrote about running across my Old Maid cards in the back of the sock drawer, I mentioned that Dad and I played gin rummy and canasta in the basement in the evenings.

When I wrote about running across my Old Maid cards in the back of the sock drawer, I mentioned that Dad and I played gin rummy and canasta in the basement in the evenings.

In fact, I recognize the back on these Blackstone cards. I might be able to remember how to play gin rummy, but I have long forgotten the rules to canasta.

In fact, I recognize the back on these Blackstone cards. I might be able to remember how to play gin rummy, but I have long forgotten the rules to canasta.

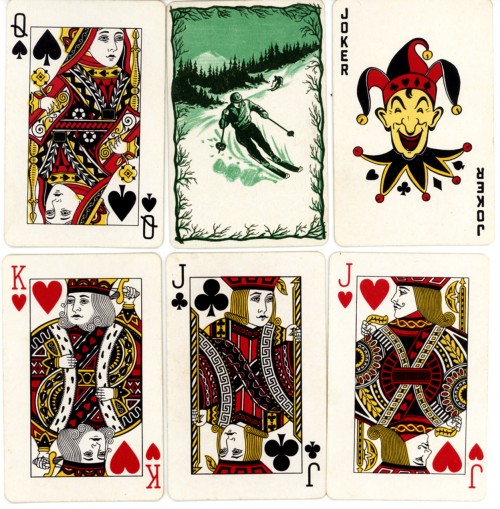

Hamilton cards had a Christmas theme

One of the two decks of these Hamilton cards is still in its original cellophane wrapper.

One of the two decks of these Hamilton cards is still in its original cellophane wrapper.

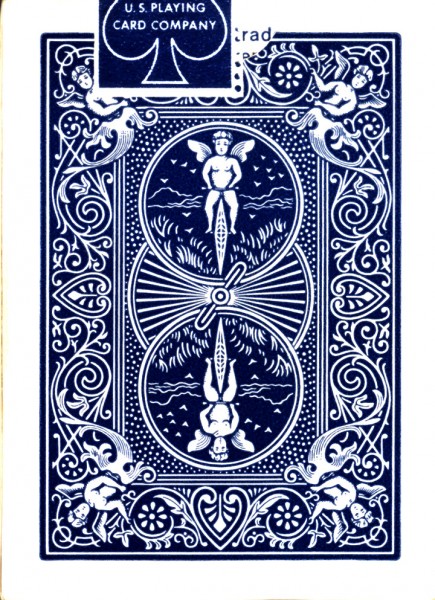

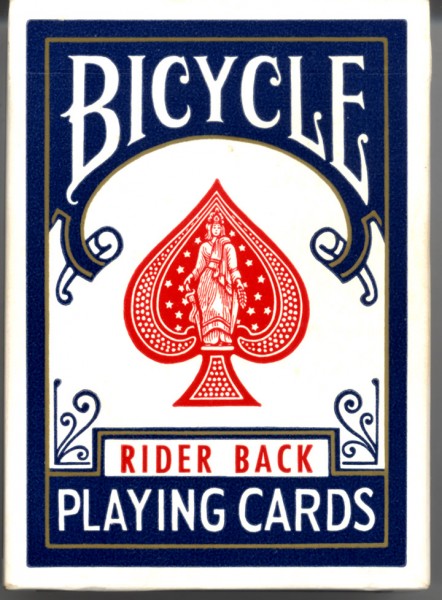

Rider Back Bicycle playing cards

There’s a good reason why these were called Rider Back Bicycle Playing cards

There’s a good reason why these were called Rider Back Bicycle Playing cards

The backs show a winged cherub riding what appears to be a bicycle. This deck’s seal is still unbroken.

The backs show a winged cherub riding what appears to be a bicycle. This deck’s seal is still unbroken.

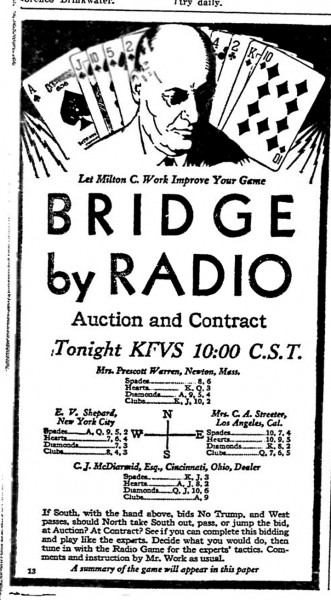

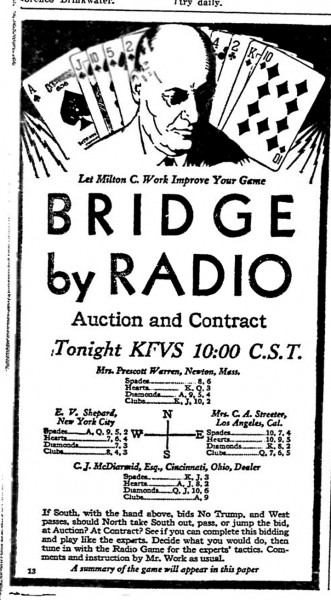

Never played bridge nor poker

I’m surprised that I was never drummed out of the newspaper business for not knowing how to play poker. That ignorance probably saved many paychecks.

I’m surprised that I was never drummed out of the newspaper business for not knowing how to play poker. That ignorance probably saved many paychecks.

Bridge was a big deal in Cape Girardeau. Here’s a front page promo for Bridge by Radio.

When I transferred into Ohio University my junior year, dorm space was tight, so I was pigeonholed into a tiny room with two freshmen. One of them was an over-privileged twirp whose obnoxiousness was trumped only by the volume of his snoring.

Fortunately, early in his college academic career he discovered all-night bridge games in the lounge. They were followed by all-day bridge games. The other roomie and I didn’t miss him when he flunked out after the first quarter.

Not much news about card games

With Cape being in the Bible Belt, I figured there would be lots of stories about card gambling. It turned out most of the busts had to do with moonshine, bootlegging, and the “operation of gambling devices.”

With Cape being in the Bible Belt, I figured there would be lots of stories about card gambling. It turned out most of the busts had to do with moonshine, bootlegging, and the “operation of gambling devices.”

Typical of the stories was one in the July 23, 1930, Missourian where “George C. (“Curley”) Norris, who for months operated a notorious roadhouse on the Bend road, was arrested for the operation of a roadhouse, sale of liquor and operation of gambling devices.” Arrested with him when he was apprehended in Poplar Bluff was Edna Conrad, who, the paper pointed out, “admitted they were not married, according to officers.”

Maybe Edna had a salacious twist like the Queen of Hearts in the Northbrook deck.

Revenue stamp dates deck

This unopened deck of Northbrook cards still sports the U.S. Int. Rev. stamp on the package. Those revenue stamps were issued between 1894 and June 22, 1965. That would mean the deck is at least half a century old.

This unopened deck of Northbrook cards still sports the U.S. Int. Rev. stamp on the package. Those revenue stamps were issued between 1894 and June 22, 1965. That would mean the deck is at least half a century old.

Mother and the slot machine

I can’t let the topic of gambling pass without repeating the story Mother always told about her girlhood.

I can’t let the topic of gambling pass without repeating the story Mother always told about her girlhood.

My grandparents owned several businesses in Advance at one time or another. One was a tavern that had a few slot machines to bring in some extra (if illegal) income. Her parents had to leave one afternoon and left her in charge. She was all of about 13 years old.

It must have been an election year, because the place suddenly filled with law enforcement officers who were going to confiscate the slot machines as being illegal gambling devices. Mother knew that one of the machines was full of money, so she stood up to the sheriff and said, “You can’t take that one. It’s broken. If it doesn’t work, it’s no more a gambling machine than that bar stool.”

They left it behind.

The coy joker

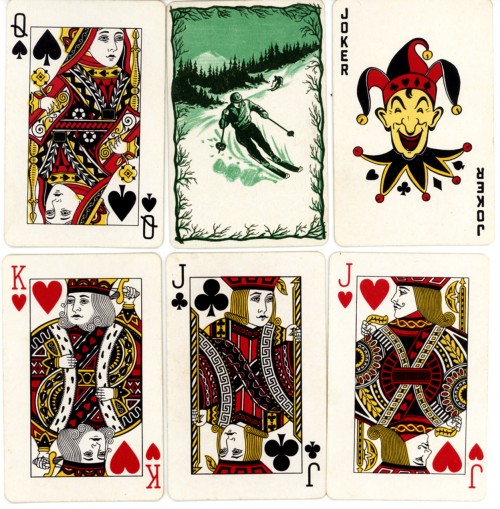

Kings, Queens and Jacks all looked pretty much the same, but Jokers could have some personality.

Kings, Queens and Jacks all looked pretty much the same, but Jokers could have some personality.

Northbrook how-to pamphlet

In case you didn’t know how to play cards or take care of them, Northbrook packaged this pamphlet with their cards. Click on any photo to make it larger, then use your arrow keys to move through the gallery.

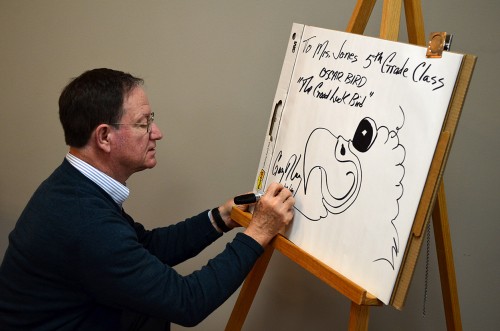

I know I did a story about the monthly “pickin'” at Jackson’s Cape County History Center recently, but I was there again Saturday night and couldn’t help shooting more pictures. It’s officially promoted as a “Traditional Music Night,” but everybody just calls it a “pickin'” where anybody with a musical instrument can sit down and play away. Miscues, false starts and forgotten lyrics add to the fun.

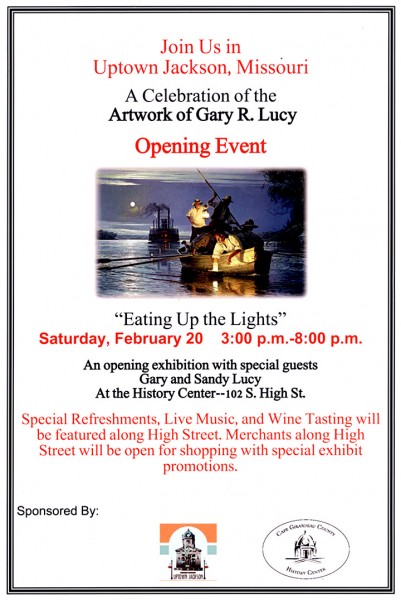

I know I did a story about the monthly “pickin'” at Jackson’s Cape County History Center recently, but I was there again Saturday night and couldn’t help shooting more pictures. It’s officially promoted as a “Traditional Music Night,” but everybody just calls it a “pickin'” where anybody with a musical instrument can sit down and play away. Miscues, false starts and forgotten lyrics add to the fun. The panels for the Gary R. Lucy exhibit took up the center portion of the room, but there was plenty of seating around the edges. If you haven’t been in to see the exhibit, it’ll be up until April 10.

The panels for the Gary R. Lucy exhibit took up the center portion of the room, but there was plenty of seating around the edges. If you haven’t been in to see the exhibit, it’ll be up until April 10. Carla’s husband Steve Jordan – better know as “Doc” – looks on while Carla sings a song with a confusing chorus that most of us were afraid to join in on because we weren’t sure what would come out if our tongues got tangled. He was born on February 29, the same date as the bass player, so they are going to be carded for a long, long time.

Carla’s husband Steve Jordan – better know as “Doc” – looks on while Carla sings a song with a confusing chorus that most of us were afraid to join in on because we weren’t sure what would come out if our tongues got tangled. He was born on February 29, the same date as the bass player, so they are going to be carded for a long, long time.