I met David Kelley in Altenburg at the Lutheran Heritage Center and Museum about the time he was helping found the Starzinger Family Research Library in memory of his long-time friend, Margaret Starzinger Wills, whose family was from the area.

I became better acquainted with him when we kept running into each other at Jackson’s Cape Girardeau County History Center, where he was creating memorials to the Talley side of his family.

How would you like to document The Bootheel?

It might have been Director Carla Jordan’s nudging that got him to broach the idea of having me document The Bootheel. I was intrigued, but not sure it was the right project for me.

Unfortunately, Mr. Kelley died of COVID, so he’ll never see the project through (and, to be honest, I’m not sure I will, either, for a number of reasons).

David E. Kelly, Sr. 1930 – 2020

What’s The Bootheel?

I guess it’s as much a state of mind as it is a geographical entity.

A Wikipedia entry defines it this way:

The Missouri Bootheel is the southeasternmost part of the state of Missouri, extending south of 36°30′ north latitude, so called because its shape in relation to the rest of the state resembles the heel of a boot.

Strictly speaking, it is composed of Dunklin, New Madrid, and Pemiscot counties.

However, the term is locally used to refer to the entire southeastern lowlands of Missouri located within the Mississippi Embayment, which includes parts of Butler, Mississippi, Ripley, Scott, Stoddard and extreme southern portions of Cape Girardeau and Bollinger counties.

It starts at the Benton Hills for me

I consider The Bootheel to begin at about MM 82.8 southbound on I-55 just north of Benton. That’s where you leave rolling hills, and gravity takes you down to the flatlands that will carry you all the way to the Gulf of Mexico, more or less.

Mr. Kelley and I drove about 1,200 miles just surveying most of the counties listed above. During that overview, I learned much from his monologues, but shot less than two dozen photos.

I had trouble wrapping my head around the region. It was the very definition of FLAT, with few places to gain any perspective. On top of that, many of the towns and villages had either disappeared or were in major disrepair.

I’m fond of shooting dying places like coal towns in SE Ohio or Cairo, Ill., but there was a dearth of places where I could feel the vibes of those who had passed through.

Pemiscot County

I can’t figure out how to show what I shot, so I’m going to post a series of random galleries, followed by links to blog posts I’ve done that might or might not put some of the images in context.

Here’s a selection of photos from Pemiscot county. Click on any image to make it larger, then use your arrow keys to move around. Escape will take you out.

Pemiscot county was where Mr. Kelley and his family raised cotton for many years, and it was the place we talked about the most.

He said that when mechanical cotton harvesters came into common use in the 1960s, the county lost about 85% of its population. When the more skilled workers fled to places like St. Louis, Chicago and Memphis, and the lesser-skilled migrated to the smaller regional towns, the stores dried up for lack of customers. When the stores folded, so did the banks and other businesses.

I felt like I had let Mr. Kelley down because I couldn’t paint a portrait of the area like we both had hoped. It wasn’t until I started looking through all the blog posts I’ve done about the region that I realized that I had been working on this for a long time, even before I met him.

Pemiscot County links

- Holland, population 229

- Principal Delmar Pritchrd and Cooter High School

- Winter wheat and a mechanical preying mantis

- A Tombstone with Harry Truman’s Signature

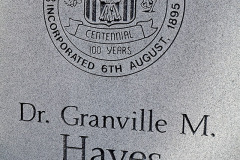

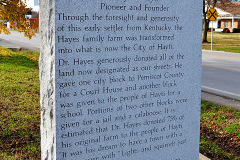

- Dr. Hayes and Hayti’s History

Mississippi County

Dad built roads in Mississippi County, and I’m pretty sure we had our trailer parked in Caruthersville or Portageville at some point.

When I was about 10 years old, he took me to where they were getting gravel delivered by railroad hopper cars. He let me crawl under the cars with a hammer to cause the gravel to fall out onto a conveyor belt that loaded it on trucks.

He told me to stay under the rail car while a bulldozer pushed the next one up into position. “Just keep low and keep your arms and legs between the rails.” Can you imagine what OSHA would say about that today?

Mississippi County links.

- Griggs-Smith-Staples Cemetery

- Big Oak Tree State Park

- Charleston Theater busted for porn

- Bird’s Point Levee

- Why do silos have holes?

Missouri – Arkansas State Line

I was curious to see if the arch was still there. We not only saw the arch, but we had a great lunch at the Dixie Pig in Blytheville. I’m pretty sure that the last time I was in Blytheville before that was in the mid-70s, when I wanted to rent a truck to carry a load of Dutchtown lumber to Florida to build a shed in the back yard.

Renting it one-way from Cape was going to cost a mint, but I found out that Arkansas had a surplus of trucks, and they wouldn’t hit me with a surcharge. The only thing was that I had to be careful of the mileage allowed, and renting in Arkansas, loading in Missouri, and driving to Florida meant I had to find the most direct route possible.

I ended up going on some backroads not normally travelled by tourists. When I gassed up at one tiny station, the kid who serviced me asked, “How much do they pay you to drive that-there truck?”

It was obvious that he had never seen a rental truck or understood the concept of one.

Here is an interesting historical nugget about the Arch area: The area around the arch became known as “Little Chicago” because of the type of activity that went on there. A long-time resident of nearby Yarbo, Arkansas, once said of the arch, “It was a good place to go while the wife and kids were in church.”

Curator Jessica meets the Hwy 61 Arch

Dunklin County

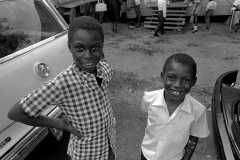

Once I established that I wasn’t some kind of pervert taking pictures of kids (apparently that had happened not long before), I got a friendly welcome from the folks at the Malden High School’s football game. The mosquitoes gave me a great welcome, too.

I also shot a reunion of people who had been stationed at the Malden Airport during World War II, but I never got around writing about it.

Malden’s Green Wave – High School Football at its best

Scott County

I never considered Scott City to be the Bootheel, but the southern parts of it, which include the north edge of Sikeston, qualify.

Scott County links

- Scott City Mill

- I-55 interchange under construction

- Scott City Fire Department #2

- Eisleben Lutheran Church

- Strange Santa Claus

- Service Station Fire

- SEMO Port Authority from the air

- Watching giant pick-up sticks at SEMO Port

- Morley and its community center

- New Hamburg’s Catholic Church

- Guardian Angel Catholic Church in Oran

- An informal Tour de Oran

- Unhappy Chaffee residents at road hearing

New Madrid County

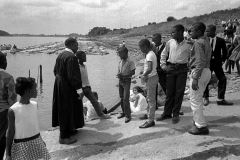

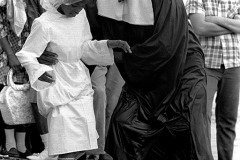

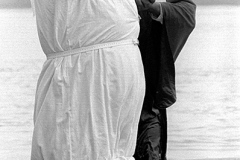

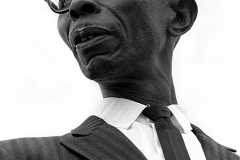

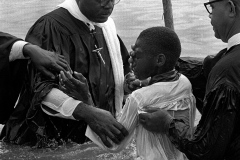

I spent a lot of time in the New Madrid area trying to track down people I photographed being baptized in the Mississippi River in 1967. Unfortunately, the exodus from the area after mechanical harvesters arrived caused a lot of them to leave.

I’m going to put the Baptism gallery at the end of the post because it contains so many images.

Cotton fields look like Christmas decorations.

A day in New Madrid with Jennifer Schwent

1965 Sikeston rodeo with Jim Nabors

More 1965 Sikeston rodeo and Jim Nabors

Old men playing checkers in Matthews

Hornersville in Dunklin County

This was one of the few small towns I was able to find much to document. I was amused to find that my parked car’s dashcam captured me wandering around the street like I was a loose ball in a pinball game.

That drove Mr. Kelley crazy. He couldn’t figure out why I couldn’t just get out of the car, snap a picture, then head out to the next destination.

That impatience eventually brought an end to our collaboration. I left him in the car while I went to chat with an old man at a mostly-abandoned cotton gin. He was a little reluctant to be photographed, but just about the time I had won him over, Mr. Kelley started honking the horn to tell me I was wasting too much time.

After that, I became a solo explorer.

Stoddard County

Most of my time in Stoddard County was spent in Advance, but because we had extended family and friends in the area, I grew up sitting on a lot of front porches hearing and overhearing tall tales about the taming of ‘Swampeast’ Missouri.

Stoddard County links

- Taming Swampeast Missouri

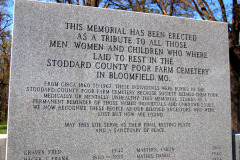

- Stoddard Poor Farm Cemetery

- Bloomfield’s Veterans Cemetery

- Stars and Stripes Museum

- Stoddard County Confederate Memorial

- The last words of Pvt. Ladd

- Cruse Cemetery near Toga

- Dexter’s Corner Stop Cafe

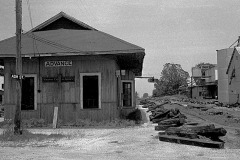

City of Advance in Stoddard County

My mother and grandparents came from Advance. Dad’s construction company once had an office in the Prather Building, along with Welch’s Liquor Store. For awhile, we lived in our trailer parked in my grandparents’ driveway.

Because of that, I have lots of random stories and photos of the town, including some of its mysteries that are still unsolved to this day.

Advance links

- Mother was in the Advance High School band and glee club

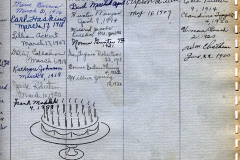

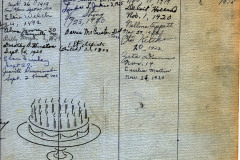

- Advance school photos from the 1930s

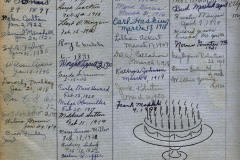

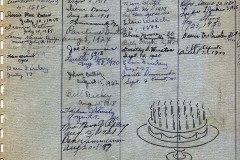

- Advance autographs from Mother’s Birthday Scrapbook

- Advance Bank robbery

- Where did the Advance tombstones go?

- Advance train depot and how town was named

- Mary O Adkins grave in Pleasant Hill Cemetery

- Big & Friendly Morgan’s

- Elfrink Truck Line

- Grandmother’s Pleasant Hill 4th grade report card

- Elsie Welch of Advance – This Is Your Life

- Charlie’s Cut-Rate-Store and the Prather Building

- 1946 interior of Welch’s Drug and Sundries

- Advance Elementary School under construction – 1966

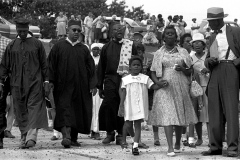

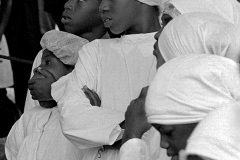

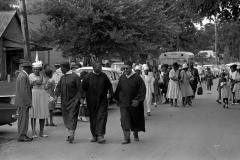

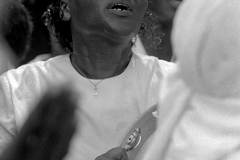

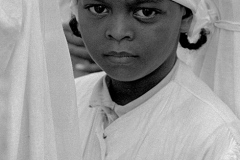

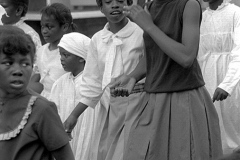

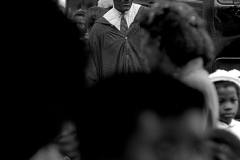

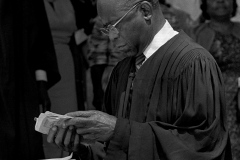

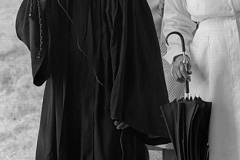

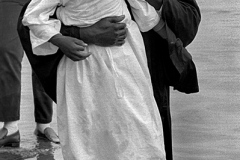

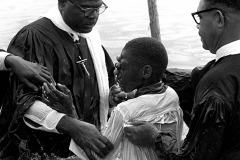

New Madrid Mississippi River Baptism

This was one of the last things I shot before transferring to Ohio University in Athens, Ohio, as a junior in 1967.

Most of the photos I had taken, up until I shot the Smelterville photos and the Baptism, were fairly pedestrian traditional newspaper photos. These two projects were the first time that my “style” started to show up.

I’ve always considered them to be my Missouri “final exam.”

I had hoped to do a Smelterville-type project where I tracked down the people in the photos, but the out-migration brought about by the change in farming methods and markets scattered most of the subjects out of the area.

I WAS able to find Bishop Benjamin Armour, one of the preachers in the river, in 2013.