I hate fires. Maybe it’s because I’m a pack rat, but I hate to see everything that someone owns go up in smoke and flames. Even if the owners have insurance, the most precious things can’t be replaced.

I hate fires. Maybe it’s because I’m a pack rat, but I hate to see everything that someone owns go up in smoke and flames. Even if the owners have insurance, the most precious things can’t be replaced.

I’m going to be sneaking away from Southeast Missouri more frequently. The Lutheran Heritage Center and Museum in Altenburg has invited me to speak on the topic of regional photography at a conference this fall, so I’m digging through stuff that I’ve taken outside Missouri. When I publish here, I’ll try to find something to say about it that will still be interesting.

The Reid Fire

The January 6, 1969, front page of The Athens (OH) Messenger contained the fire shot at the top, along with a short news story with the 5Ws and H basics. On what we called The Picture Page, I ran three other photos.

The January 6, 1969, front page of The Athens (OH) Messenger contained the fire shot at the top, along with a short news story with the 5Ws and H basics. On what we called The Picture Page, I ran three other photos.

A Home Dies

Sometimes it’s harder to write a short caption that it is a long one. I hate to think of how many times the floor around my desk was covered up with wadded-up carnations of false starts.

Sometimes it’s harder to write a short caption that it is a long one. I hate to think of how many times the floor around my desk was covered up with wadded-up carnations of false starts.

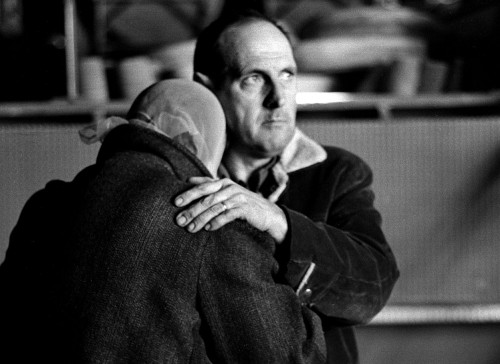

This wasn’t one of those nights. When I got back to the office, I slid a piece of copy paper into our battered old manual typewriter and banged out, “The Reids watched their home die last night. A man at the fire said nobody was hurt. He was only partly right. -30-“

I don’t know if that was good journalism, but it was how I felt sitting there smelling of smoke and still shivering from the cold, grateful that I had a house to go home to.

How do you cover a fire?

Hang around a fire station long enough and you’ll hear a firefighter use the term “good fire.” He or she doesn’t mean that they enjoy seeing someone’s home or business burn. What they mean is that “a good fire” is one that tests them and their abilities.

Hang around a fire station long enough and you’ll hear a firefighter use the term “good fire.” He or she doesn’t mean that they enjoy seeing someone’s home or business burn. What they mean is that “a good fire” is one that tests them and their abilities.

Photographers use the same language. That doesn’t mean that you don’t ache for the people you are photographing; it just means that you have to channel that empathy towards creating an image that will bring that tragedy home to the reader. You exist in a strange gray area where you aren’t a spectator, but you also aren’t a participant. You are the eyes of the community.

I tried to be as unobtrusive as possible. In this case, I shot available light so I wasn’t popping a flash in their faces and I used a medium telephoto lens so I could stay back 15 or 20 feet.

“I was busy trying not to die”

I tried to salve my conscience by telling myself that my photographs might cause the community to rally to the family’s aid. After the fact, I’ve talked with victims of tragedies to see if my presence caused them any distress.

I photographed a highway patrolman being worked on by medics after he had been shot at a traffic stop, then I requested the assignment to cover his recuperation. On our first meeting, I took along a photo of him on the ground. “Did it bother you when I took this photo?” I asked him.

“Actually, I was so busy trying not to die that I didn’t even notice you were there,” he said with a twist of a smile.

A salute to the chimney savers

Small rural fire departments made up mostly or all of volunteers are sometimes called “chimney savers” because that’s often all that’s left at the end. That’s not the fault of these guys who put their lives on the line. By the time the volunteers get to the station, crank up the truck and arrive on the scene, a lot of time has passed. The three and four-minute response times we’re used to in cities might be 15 to 30 minutes in the country. On top of that, it’s unlikely that there will be a fire hydrant nearby. Water has to be relayed from where there is one or a pond or stream has be be drafted for a water supply.

Small rural fire departments made up mostly or all of volunteers are sometimes called “chimney savers” because that’s often all that’s left at the end. That’s not the fault of these guys who put their lives on the line. By the time the volunteers get to the station, crank up the truck and arrive on the scene, a lot of time has passed. The three and four-minute response times we’re used to in cities might be 15 to 30 minutes in the country. On top of that, it’s unlikely that there will be a fire hydrant nearby. Water has to be relayed from where there is one or a pond or stream has be be drafted for a water supply.

If I got there about the same time as the truck, I’d set my camera aside to help the firefighters pull hose and get set up. Part of that was so they’d be more likely to help me get my story and photos; part of it was because that’s what you do in a small town. I also served as an extra set of eyes for them. Because I wasn’t actively involved in squirting wet stuff on red stuff, I could warn them of power lines, signs of a flashover or a wall or roof that looked like it might collapse.

Photo gallery of a fire

Here’s a selection of photos from that cold January night. It’s been 43 years since I last looked at these pictures. I see things in them today that I didn’t see when I edited the film originally. After I had made my selection of the two family photos that ran in the paper, I tuned out the other frames. I didn’t realize until 2012 the range of emotions I had captured.

I’m glad I’m not chasing sirens anymore. It’s been a long time since I’ve used the phrase “good fire,” too. Click on any photo to make it larger, then click on the left or right side of the image to move through the gallery.

The negative sleeve says “airport fire truck 6/12/67.” The Missourian didn’t have any stories about it for a couple days on either side of that date, so I assume it was just something I spotted and snapped off nine frames before moving on. (Click on any photo to make it larger.)

The negative sleeve says “airport fire truck 6/12/67.” The Missourian didn’t have any stories about it for a couple days on either side of that date, so I assume it was just something I spotted and snapped off nine frames before moving on. (Click on any photo to make it larger.) If the water source isn’t close to the fire, then the water has to be shuttled from the pond to the fire using a series of trucks. For long distances, two or more pumpers could be spaced out over a long run of hose to boost the pressure. That takes a LOT of hose and a lot of manpower. That’s one reason why rural volunteer fire departments were called “chimney savers.” By the time they could get to a fire, establish a water supply and a resupply, too often a chimney would be the only thing left standing. That’s not to criticize the firefighters who were putting their lives on the line; it was just a fact of life.

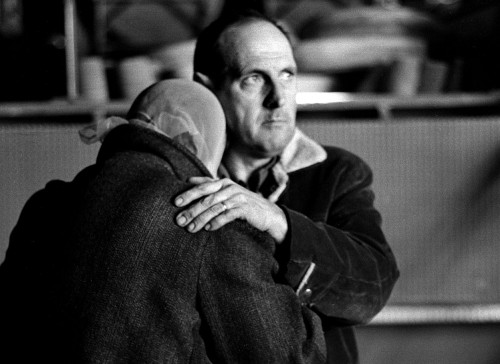

If the water source isn’t close to the fire, then the water has to be shuttled from the pond to the fire using a series of trucks. For long distances, two or more pumpers could be spaced out over a long run of hose to boost the pressure. That takes a LOT of hose and a lot of manpower. That’s one reason why rural volunteer fire departments were called “chimney savers.” By the time they could get to a fire, establish a water supply and a resupply, too often a chimney would be the only thing left standing. That’s not to criticize the firefighters who were putting their lives on the line; it was just a fact of life. Murphy’s Law works in town, too. These two Gastonia, N.C., firefighters are looking down the street for the surge of water that’s going to charge their hose. It never came. There was a problem with the nearest hydrant. By the time a supply line was laid from the next nearest hydrant, the house was a loss. You can tell from their expressions how frustrated they were.

Murphy’s Law works in town, too. These two Gastonia, N.C., firefighters are looking down the street for the surge of water that’s going to charge their hose. It never came. There was a problem with the nearest hydrant. By the time a supply line was laid from the next nearest hydrant, the house was a loss. You can tell from their expressions how frustrated they were.