When Curator Jessica and I headed up to Kent, Ohio, in 2014, she insisted on a side trip to see Big Muskie’s bucket at the Miners’ Memorial Park. Click on the photo to make it large enough to see her IN the bucket.

When Curator Jessica and I headed up to Kent, Ohio, in 2014, she insisted on a side trip to see Big Muskie’s bucket at the Miners’ Memorial Park. Click on the photo to make it large enough to see her IN the bucket.

John Prine’s Paradise

The youngster had never heard John Prine singing Paradise, an ode to a town hauled away by Mr. Peabody’s coal train and bought out by the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA).

Now, she wanted me to carry her off to Paradise. The first OH-MO-OH trip was plagued by fog, drizzle and downpour, so we had to bail. The weather was OK on this one, but we were pushing darkness pretty hard, particularly since we were looking for something that wasn’t there.

We found the TVA

The first clue that we might be close to the right place was when we spotted the mammoth cooling towers of the TVA’s Paradise Fossil Plant. An interesting website postulates that Mr. Peabody’s coal trains might have hauled Paradise away, but it was the power plant that was the nail in the coffin:

The first clue that we might be close to the right place was when we spotted the mammoth cooling towers of the TVA’s Paradise Fossil Plant. An interesting website postulates that Mr. Peabody’s coal trains might have hauled Paradise away, but it was the power plant that was the nail in the coffin:

“The Paradise Fossil Plants were built and started raining ash and debris down upon the remaining citizens of Paradise. Concern arose for the health of the remaining residents of Paradise. Obviously having ash created during the factory process and pouring from the air like warm, toxic snow was not a positive influence for ones respiratory system. Most likely, to prevent an onslaught of environmental and residential poisoning lawsuits, the Tennessee Valley Authority stepped forward. TVA representatives convinced the remaining townsfolk to vacate and paid them minuscule amounts to abandon their once happy lives in Paradise.”

Power plant went online in 1963

The TVA website said Units 1 and 2 went online in 1963. They were the largest operating units in the world at the time. A third powered up in 1985. The two older units will be idled by the end of 2017, replaced by a $1 billion gas-fired plant under construction in the distance.

The TVA website said Units 1 and 2 went online in 1963. They were the largest operating units in the world at the time. A third powered up in 1985. The two older units will be idled by the end of 2017, replaced by a $1 billion gas-fired plant under construction in the distance.

The hunt for the cemetery

One website we read said a cemetery was about all that was left of the original community. We poked around the power plant, wondering how long it would be before somebody from Homeland Security showed up to ask these flatland furiners with Florida tags why they were creeping around, occasionally taking photos. We took off down a promising road that kept getting progressively smaller and bumpier.

One website we read said a cemetery was about all that was left of the original community. We poked around the power plant, wondering how long it would be before somebody from Homeland Security showed up to ask these flatland furiners with Florida tags why they were creeping around, occasionally taking photos. We took off down a promising road that kept getting progressively smaller and bumpier.

After passing a washtub-sized snapping turtle, a deer and a pair of amorous squirrels, I spotted a guy in his carport with a couple of kids around him. When I turned into his lane, my curator partner said, “This one is yours.”

I allowed as how Kentucky coal miners would probably be as friendly as Appalachian coal miners, but I mentally adjusted my dialect, taking a little Yankee out of my SE Ohio twang, and dialing some North Carolina into my Swampeast Missouri drawl. The gentleman couldn’t tell me exactly where we needed to go, but he gave us some hints, peppered with local landmarks of the “third dead skunk” variety.

You gotta be kidding

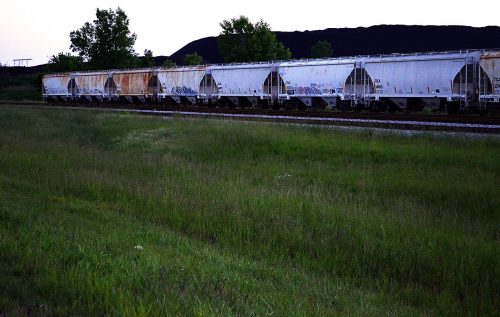

We headed back past the snapping turtle, past the power plant and back toward huge mounds of coal and the railroad cars that hauled it. Right about here, my navigator said, “Turn left.”

We headed back past the snapping turtle, past the power plant and back toward huge mounds of coal and the railroad cars that hauled it. Right about here, my navigator said, “Turn left.”

I did, taking us up a vertical gravel road that deadended at the top of a hill with a radio tower on it. While trying to figure out how to turn around, Navigator said, “That looks like a road going down the hill.”

I might have been able to go DOWN that hill, but there was no way we’d ever be able to drive back up it. Sometimes you have to disregard your navigator because I could hear Johnny Cash singing about what was going to happen if we went down that road that was Dark as a Dungeon:

And pray when I’m dead and the ages shall roll

That my body would blacken and turn into coal

Then I’ll look from the door of my heavenly home and pity the miner digging my bones

The McDougall Family

We headed back toward the power plant and found the road that led past the McDougall / Paradise Cemetery

We headed back toward the power plant and found the road that led past the McDougall / Paradise Cemetery

The McDougalls, I assume of the family for which the cemetery was named, had plots surrounded by an intricate metal fence. They weren’t on the highest part of the burying grounds, nor were they in the mowed section, but the fence made up for it.

A grammatical error

John McDougall, born in Scotland in 1821, and who died in Muhlenberg county 60 years later, has been sleeping under a stone with a typo. Above the digit pointing to heaven, is the inscription, “THEIR IS REST.”

John McDougall, born in Scotland in 1821, and who died in Muhlenberg county 60 years later, has been sleeping under a stone with a typo. Above the digit pointing to heaven, is the inscription, “THEIR IS REST.”

Eudoxia Smith Robertson

A significant number of the stones had birth and death dates in the 1800s. Eudoxia Smith, for example, was born in 1815, and married Alney McLean Robertson in 1837. She died two years later, after giving birth to two children.

A significant number of the stones had birth and death dates in the 1800s. Eudoxia Smith, for example, was born in 1815, and married Alney McLean Robertson in 1837. She died two years later, after giving birth to two children.

Kneeknockers

The thigh-high grass hid lots of shin and knee-high gravestones. I found this one particularly attractive, probably because I saw it before I felt it.

The thigh-high grass hid lots of shin and knee-high gravestones. I found this one particularly attractive, probably because I saw it before I felt it.

Miz Jessica and I were pleasantly surprised to find ourselves chigger-free the next morning. I was afraid we’d pick up a bunch of ticks and itchy things wading through the high grass.

Peabody Wildlife Management Area

After you have, as John Prine sings, “come with the world’s largest shovel, tortured the timber and stripped all the land,” what do you do? Well, it appears that you smooth some of the bumps, plant some grass and call it the Peabody Wildlife Management Area.

After you have, as John Prine sings, “come with the world’s largest shovel, tortured the timber and stripped all the land,” what do you do? Well, it appears that you smooth some of the bumps, plant some grass and call it the Peabody Wildlife Management Area.

Here’s a reason I’m cranky about strip mining.

Still a lot of scarring

In fairness, on our hunt for the Weir Cemetery, we managed to see two herds of deer in about two minutes, so there IS wildlife. A Google Earth view of the area still shows an awful lot of scarring left behind.

In fairness, on our hunt for the Weir Cemetery, we managed to see two herds of deer in about two minutes, so there IS wildlife. A Google Earth view of the area still shows an awful lot of scarring left behind.

After a couple false starts, we finally found our second cemetery.

Weir Cemetery

The Weir cemetery was well-maintained. It had a small parking lot nearby and there was evidence of recent landscaping. The FindAGrave website said the cemetery is known as both the Doug Weir and the Vanlandingham Cemetery. We saw some stones with that name on them.

The Weir cemetery was well-maintained. It had a small parking lot nearby and there was evidence of recent landscaping. The FindAGrave website said the cemetery is known as both the Doug Weir and the Vanlandingham Cemetery. We saw some stones with that name on them.

That flag is one of the reasons I tweaked the Ohio Yankee out of my accent. This IS Kentucky.

Markers decorated with shells

This row of stones were interesting because the markers had small shells embedded in the concrete. I had to assume they were mussel shells from the nearby Green River (where Prine said “the air smelled like snakes”).

This row of stones were interesting because the markers had small shells embedded in the concrete. I had to assume they were mussel shells from the nearby Green River (where Prine said “the air smelled like snakes”).

Starting to get dark

This little excursion had been fun, but the sun was sinking faster than I liked, and we still had another 170 miles to go to get to Cape.

This little excursion had been fun, but the sun was sinking faster than I liked, and we still had another 170 miles to go to get to Cape.

It was time to put Paradise behind us.