Reader Madeline DeJournett posted a link on Facebook to a Psychology Today story entitled “What Learning Cursive Does for Your Brain.” The story whines that schools are phasing out the teaching of cursive writing.

Reader Madeline DeJournett posted a link on Facebook to a Psychology Today story entitled “What Learning Cursive Does for Your Brain.” The story whines that schools are phasing out the teaching of cursive writing.

Madeline, a former school teacher, opines: “Can you imagine that they would give it up? It is a sad state of affairs, when our dependency on technology and machines cause us to abandon basic traditional skills like writing!”

“Good riddance,” says me. I started typing in the first grade or thereabouts. By the time I was in the third or fourth grade, I was a proficient hunt ‘n’ peck typist. I tried to learn touch typing by doing exercises when I got high school age and got where I can mostly type without looking at my hands, but it ain’t pretty.

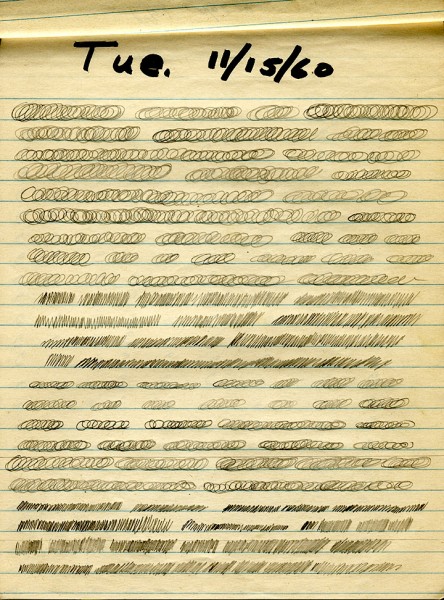

Dad had the most beautiful handwriting you would ever want to see. It appalled him to see my chicken scratching, so he embarked on a campaign in the fall of 1960 to improve my writing. I had to do several pages of drills every day. They started out with curves and lines.

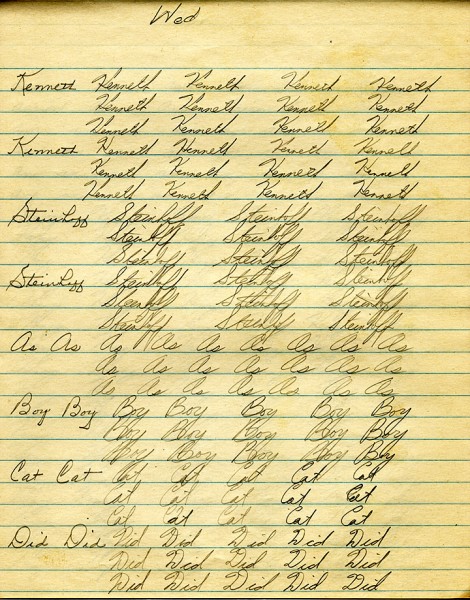

Then we moved on to words

Dad would write an example, then I would have to copy it for three lines. His letters weren’t formed exactly like we were taught in class, but they were like artworks. Mine were more like modern art.

Dad would write an example, then I would have to copy it for three lines. His letters weren’t formed exactly like we were taught in class, but they were like artworks. Mine were more like modern art.

Long about that time, I was in Pastor Fessler’s Confirmation Class. His standing Monday assignment was for us to hand in a 150-word summery of his Sunday sermon. That turned out to be the most useful thing I got out of Confirmation. I learned how to take good notes in my own personal scrawling, then go home to the typewriter where I would bang out exactly 150 words. Not 149, not 151. Exactly 150. I have no idea if he actually counted the words (or even read them), but it was a point of pride to hit the number on the nose.

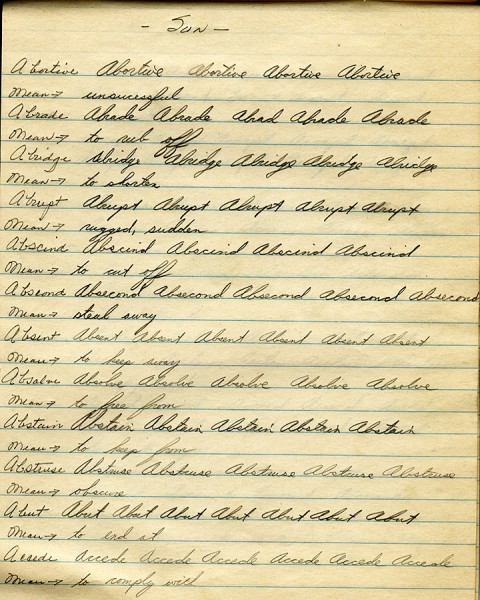

Building a vocabulary

When I complained about the finger exercises, Dad gave me a new assignment: he’d write a word out of the dictionary, I’d have to copy it, then define it. My handwriting didn’t improve, but my vocabulary certainly did.

When I complained about the finger exercises, Dad gave me a new assignment: he’d write a word out of the dictionary, I’d have to copy it, then define it. My handwriting didn’t improve, but my vocabulary certainly did.

I found only one notebook of writing practice, so I suspect that Dad finally gave me up as a lost cause. I think I didn’t make an effort because I knew I’d never be able to write as well as he did.

How did my writing turn out?

I got into a business where you had to write quotes all the time. I developed my own shortcuts and abbreviations that probably nobody else could decipher, but worked for me.

I got into a business where you had to write quotes all the time. I developed my own shortcuts and abbreviations that probably nobody else could decipher, but worked for me.

A couple of days ago, I stumbled across a box of my old notebooks from the late 60s and was amazed at how some of those scrawls transported me back in time. I saw a quote from an old man describing a big coal mining disaster in Southern Ohio. “It put black crepe on every home in the valley.” Even if I didn’t have a physical photograph of the man, that sentence popped him into my mind. He’s long dead, but his words live on in my notebook.

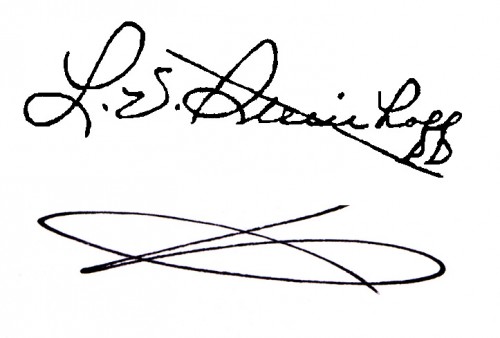

Probably the best answer to the question, “How did my writing turn out?” would be answered by comparing Dad’s signature with mine. (In case you can’t quite make it out, the second line reads “Kenneth L. Steinhoff.)

Sorry, Dad.