The evening I shot the St. Vincent’s Catholic Church at sunset, I turned the camera in the other direction (standing in almost the same spot) and took this photo of a radio tower that stands along the railroad tracks. (Click to make it larger.)

There was something about the blue sky, the silhouetted tower and the microwave dish that looked like a flying saucer on its side that appealed to me. When I enlarged the frame, there were streaks of birds flying by (or they might have been mosquitoes; they were that big that night).

Sky would turn black with birds

That reminded me of the huge flocks of starlings that would turn the skies over Cape black at dawn and dusk in the 1960s. They would fly over the house making the most raucous screeching sounds. Then, as suddenly as they had appeared, they were gone. I stood out in the yard blasting away with my Daisy BB gun a few times, but quickly realized I’d never hit anything.

The birds made the news in 1965, when folks in Dexter started testing positive for histoplasmosis, a lung disease attributed to fungus in the droppings and soil underneath the roosting areas used by several million starlings and blackbirds. A March 24, 1965, Missourian story said that the birds had been roosting on a 20-acre tract near the city for the past five winters.

The birds made the news in 1965, when folks in Dexter started testing positive for histoplasmosis, a lung disease attributed to fungus in the droppings and soil underneath the roosting areas used by several million starlings and blackbirds. A March 24, 1965, Missourian story said that the birds had been roosting on a 20-acre tract near the city for the past five winters.

Eight million birds near Dexter

A five-acre tract near Frisco, about 1-1/2 miles south of Essex, had also been a roosting area for an estimated three to five million birds. It was estimated that as many as eight million birds were nesting around Dexter.

I did a tongue-in-cheek story about suggestions the city had received for taking care of the bird problem. They ranged from the bizarre to the impractical. One, I recall, was to spray them with detergent from the air in the wintertime so that water would penetrate their feathers and they’d freeze to death. The problem with most of the solutions, a city official said, was “what do you do with two million dead blackbirds?”

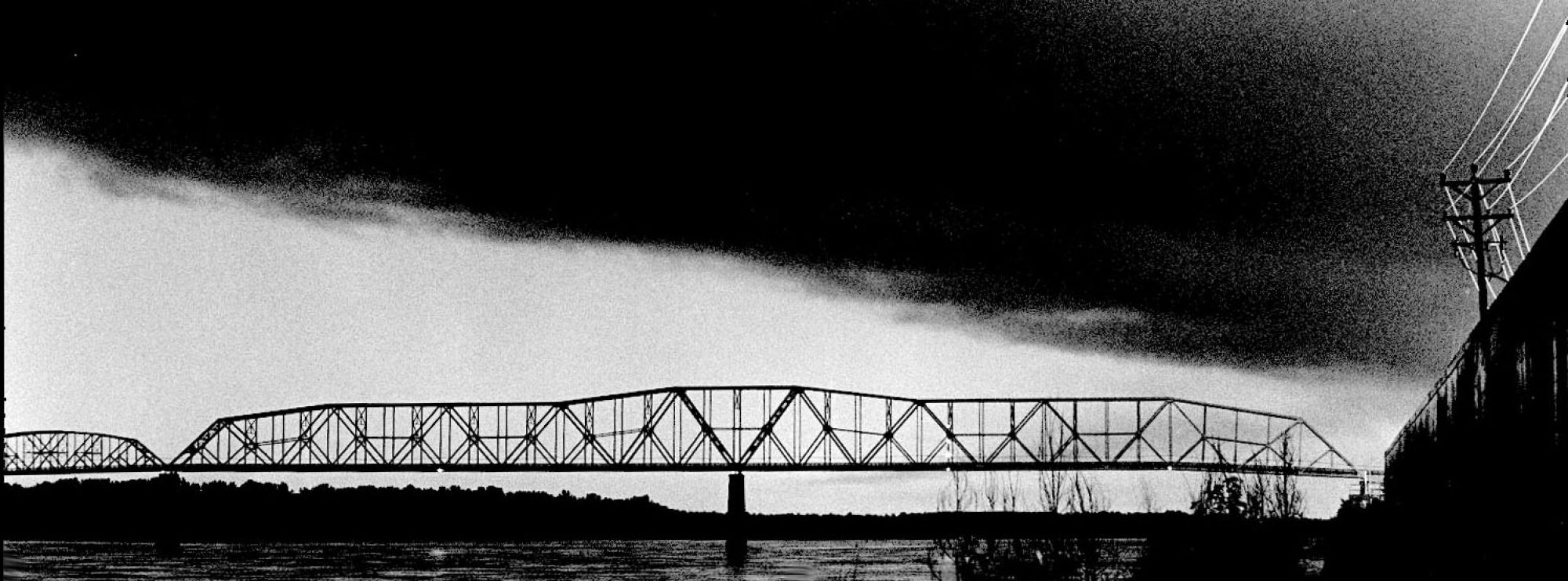

Birds roosted on bridge

Another story quoted Marvin Campbell, Cape County sanitation officer, as saying that the main roosting place for the Cape Girardeau starlings appeared to be the Mississippi River bridge. Evidence was found that thousands of birds frequented it. The problem wasn’t as great then as it had been in previous years when the birds roosted on State College property, he continued. (I wonder if that’s where the Home of the Birds got its name?)

Another story quoted Marvin Campbell, Cape County sanitation officer, as saying that the main roosting place for the Cape Girardeau starlings appeared to be the Mississippi River bridge. Evidence was found that thousands of birds frequented it. The problem wasn’t as great then as it had been in previous years when the birds roosted on State College property, he continued. (I wonder if that’s where the Home of the Birds got its name?)

Ridding the bridge of the birds was going to be complicated because authorities from both Missouri and Illinois would have to be involved. Songbirds were mixed in with the starlings, so mass extermination was not an option.

I suspect that development eliminated most of the nesting areas and the birds either died off or moved on.