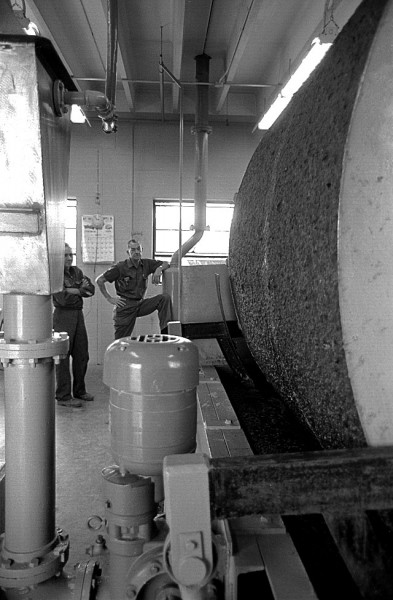

The Missourian ran one of my pictures and a story about construction resuming on a new floculator settling basin at the city’s water plant on East Cape Rock Drive. The caption said Missouri Utilities planned to build an additional clarifier,similar to the basin at top right. Water mixed with chemicals was pumped into tanks and the mud settled to the bottom.

The Missourian ran one of my pictures and a story about construction resuming on a new floculator settling basin at the city’s water plant on East Cape Rock Drive. The caption said Missouri Utilities planned to build an additional clarifier,similar to the basin at top right. Water mixed with chemicals was pumped into tanks and the mud settled to the bottom.

Preparing for population of 50,000

The July 8, 1967, story said the expansion was to prepare for the day when Cape’s population would reach 50,000. [The 2011 Census pegged Cape at 38,402. It still has a ways to go.]

The expansion was going to increase the city’s water output by 150 per cent. The original water plant was designed to hand about 3 million gallons of water a day, enough for about 31,500 persons. During the previous summer’s heat wave, the plant hit a peak of 3,880,000 gallons a day, exceeding its theoretical capacity. The improvements were to boost capacity to 4-1/2 million gallons a day.

Water comes from Mississippi River

Production engineer Fred N. LaBruyere said a pump used to pull water 1,900 feet from the river to the treatment plant would be replaced. The last major construction work took place in 1954, he said, and it was to improve the quality of the water, not the quantity.

[I hate to think what it tasted like before 1954. Cape water used to taste like chlorine with a few drops of water added.] I believe I read recently that all of Cape’s water comes from wells, not the river, these days.

Over the years, I got to cover the whole range of Cape liquids from the water treatment plant at the head end to the sewage treatment plant at the —uhhhh— other end.

Here are a few of the posts:

- Water plant goldfish pond

- Sewage treatment plant

- Dad’s scrapbook pictures of 1940-41 sewer project

- Under Cape’s streets